Why We Shouldn't Try to be Perfect Mothers

'Dear Sebastian,' the letter began in a childish script. 'Thank you very much for my Birthday Present. I love 'Angelina Ballerina' books. Love Yore God Daughter Eleanor'.

I laughed. As any mother reading this will know, the likelihood that my husband Sebastian would have a) known it was his god-daughter's birthday b) sent her a present and c) known that she liked Angelina Ballerina would have been as likely as me going six rounds at the pub.

For the truth is, while women have made huge strides in the workplace, many men have not made commensurate progress at home. Domestic responsibilities, by which I don't just mean 'childcare' but the million tiny acts of kindness and arduousness that make up life at home, are largely still done by mothers. Confusion reigns between couples about how duties should be divided. The answer for many women is just to get on with it.

Pressure for perfection

For some, the pressure of trying to achieve perfection both at home and work is proving too much - a case of 'death by a thousand cuts' as my own mother puts it.

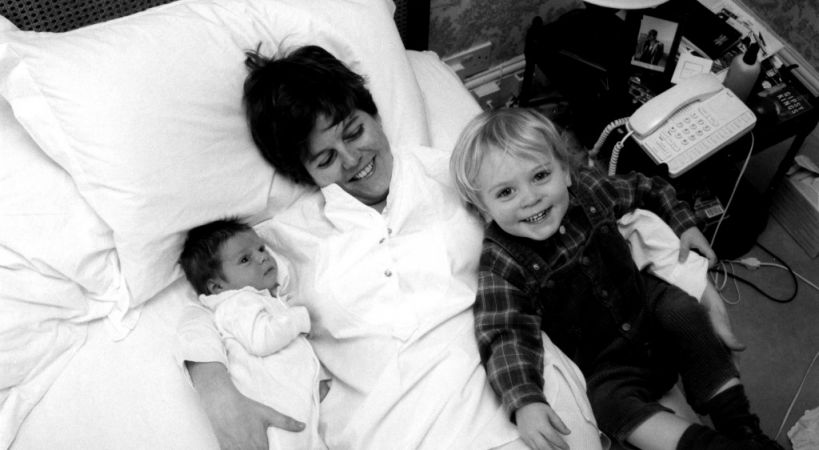

So it proved for me. The pressure I put on myself to be not just a mother, but a good one; not just to hold down a job (as a Times reporter) but to have a career; not just to be a wife, but to be supportive and loving one, in the end overwhelmed me.

Over the past 17 years I suffered two breakdowns and have had a long-running battle with depression. The first depressive episode left me bedridden for six months, the second for a year. This is the subject of my memoir, Black Rainbow. The last decade has seen me learn how to keep my own Black Dog on a tight leash. Mercifully, I now seem to be able to manage my depression.

My own forthrightness has encouraged that of others. Many mothers at the school gates have confided that they too suffer from high levels of anxiety and depression and they too are struggling with the pressure they feel to be perfect mothers. They are relieved to identify with and open up to a fellow sufferer.

I say mothers at the school gates, because although the World Health Organisation assures us that “Overall rates of psychiatric disorder are almost identical for men and women," there's no denying more woman have come forward to talk about their depression. You could well say this reflects men's traditional reticence, or that men manifest their inner stress differently from women. You could equally come to the conclusion that women struggle more than men.

Certainly the numbers suggest this. January 2014 figures from the NHS show that in 2013 almost 475,000 women were referred for counselling or behavioural therapy compared to only 274,000 men. Earlier surveys according to mental health charity SANE suggest that depression is almost twice as common among women as men.

What then is the answer? I have been forced by mental ill-health to impose limits on the way I live: good mental health maintenance means watching what I eat, getting a certain amount of sleep, and cutting out alcohol entirely. I treat myself rather like a nervous pet, have trimmed back my life, and recognise the need for a lie-down when it occurs. I've replaced life in an office with freelance writing and voluntary work in prisons and hospitals supporting those with poor mental health: I am entirely the beneficiary, given the well-known benefits of trying to help others. Therapy, drugs, and the healing power of poetry have all played their part in my recovery.

Replace 'good' with 'good enough'

I have also been forced to reassess my relations with others: we know women are especially vulnerable to depression given the pressure they put on themselves to maintain friendships and other relationships. My new attitude to all important relationships, including that with my husband and friends, but especially with my children, is to aim to replace 'good' with 'good enough'. In 1965, when women had yet to become a sizeable presence in the workforce, mothers spent 3.7 fewer hours per week on childcare than in 2008, even though women in 2008 were working almost three times as many paid hours, according to American research. ('All Joy and No Fun: The Paradox of Modern Parenting' by Jennifer Senior.)

These women were like I used to be, ferrying children to ballet classes, watching every match, supervising homework and responding to every need of the priceless modern child. I've learnt that not only can I not manage; my hothousing parenting and ensuing stress may not have pleased my children either. A 1999 survey of children of working parents conducted by the American Families and Work Institute found that ten per cent of the surveyed children wanted more time with their mothers, 16 per cent wanted more time with their fathers, but 35 per cent said they wished their mothers were less stressed.

Some of my friends can manage all the roles they and society require of them, and all credit to them. But I am a cautionary tale to those like me who have an underlying tendency to depression and anxiety and whose life falls into the quicksand of modernity with its multiple demands. Next time, I plan to get my husband to buy Eleanor's present.