Who of us has not been following the unfolding saga of Prince Harry's memoirs? We may resent the amount of media coverage and feel that there is no escaping the story, yet we may also feel drawn to reading more and more details in a mixture of bewilderment and morbid fascination. Even those of us who do not have more than a fleeting interest in the royal family find it difficult not to react and difficult not to take sides. We may be feeling protective of one party, enraged on the part of another, engaged in the lives of people we do not know, but who have been part of the cultural backdrop for most of our lives.

Why has this story such a power to emotionally both engage and enrage?

I should state straight away that I am not going to offer any opinions of a personal or professional nature on what I think may be going on for the participants in this story. I do not know any of them and an armchair psychotherapist's perspective on people who are just known as public figures is not an inspiring sight! What fascinates me though is our reaction to this story.

Even a cursory glance at social media platforms and the stream of posts regarding this story shows that people are in the grip of strong feelings and are taking sides in a quite passionate way. It is as if something about this story chimes powerfully with us: this is about families, about sibling relationships, about what happens when the wheels come off, and we recognise something of ourselves in that.

A closer look reveals a curious aspect of this particular family drama: we do not know any of the players, but we do know the archetypal roles that they have been allocated. There we have the wicked stepmother, as opposed to the beautiful young mother, who, having died young, holds all the qualities of the "good" mother.

There we have the fight between two brothers, a fight ultimately about who the true heir to the "good" mother is, her favourite, the true son.

Then we have the usurper, the newcomer to the family, poisoning family relationships, the wicked stepmother stereotype matched by the wicked daughter-in-law stereotype.

It does not matter whether any of this is true, but we all know deep down the power of such archetypal vacancies in families and how they can be activated in the reality of any family. Fairy tales may end with everybody living happily ever after, but they do ultimately refer to much more complicated and darker aspects of family life. So if we hear about two brothers fighting, physically or through publishing memoirs, those of us who have grown up with siblings know about the visceral quality of love, jealousy and rivalry between siblings, about feeling victorious or shamed, that grows out of having to learn how to share parental love. We understand how deep the scars can run that tell the story of feeling we were loved less, understood less, celebrated and enjoyed less by a parent than our siblings were.

In my consulting room I come across this all of the time, seeing adults reduced to the level of toddler rage and anguish in conflict with their adult siblings, but more importantly seeing the world and themselves shaped by this perspective: forever entering relationships as the older sister, and in that role organising and caring and taking responsibility, or the baby brother, demanding adoration and expecting others to clear up any mess left behind, or the "difficult" disappointing child, having to compensate and work extra hard, never trusting approval or taking it for granted. It never leaves us and when we see it in others, even if just in public figures, we respond. We "know"!

There are flashpoints in a family life cycle where these dynamics come powerfully to the fore. Weddings, funerals and parental wills, or just family occasions like Christmas can set fire to what seems to have been a perfectly adult arrangement of relationships.

Sometimes the flashpoint is created by a newcomer to the family, another feature of this royal drama. What may have been an arrangement that every member of the family was used to and took as "normal", may suddenly be seen differently when a newcomer introduces a new perspective. It does not matter what actual role Meghan played in the reality of the royal family, we will see her and project into her what chimes with our own experiences and fears.

In my interviews with mothers and their stories of adult newcomers to their families, their daughters-in-law and sons-in law, the fear of the newcomer taking their child away or causing estrangement between siblings or generally rejecting the family culture, was ever present. Mothers were very aware, particularly with daughters-in-law, of the power of the newcomer to strengthen or destroy family links. This is a very active and powerful crisis point in any family life cycle. No surprise then that when we see a family story unfolding in front of our eyes, it triggers an emotional response that has so much more to do with our own experience than with anything that we could possibly know about the public figures we are reading about.

Then there is the theme of good mothers and bad mothers, beautiful good mothers dying young and wicked stepmothers taking their place: there is hardly a Grimm's fairytale that does not deal with this theme. We do know that these stereotypes are on one level dealing with the devastating experience of loss of a parent, the deep and terrifying feeling of having lost an existential anchor and being unprotected and unmoored in the world. The wicked stepmother represents the danger that we are not protected from anymore at this point, the real possibility that we may me thrown out to sea. Again in my work I can see the long lasting emotional fall out of such early bereavements.

On another level these stereotypes of the good mother and the wicked stepmother deal with our need to come to terms with our ambivalent feelings towards the parent we do keep, the one that we sometimes love and sometimes hate, whom we both need and fight and who we need to separate from. How much easier it can feel to split that parent into the good and the bad, the idealised perfect "good" mother and the "bad" mother, the latter represented in fairy tales and in our own unconscious as the wicked stepmother.

Diana and Camilla are slotted into these blueprints, and whatever the reality of the story, again we think we know something, because it runs deep through our own psyche, thus filling what we cannot know with thinking we do know, and in doing so getting emotionally engaged. One might feel fascinated with the royal story or just sad when remembering that these are real people being caught in this drama in front of our eyes. Our reaction to this however tells us a great deal more about ourselves than about them.

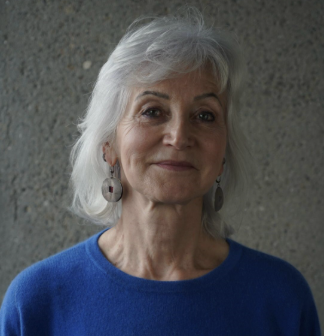

Annette Byford is a verified Welldoing psychotherapist and the author of Once a Mother, Always a Mother