Who am I, in this language?

Many people who speak more than one language notice how their sense of self subtly shifts depending on the tongue they are using. Perhaps you feel more confident in English, softer in your native language, or somehow more detached in a language you learned later in life.

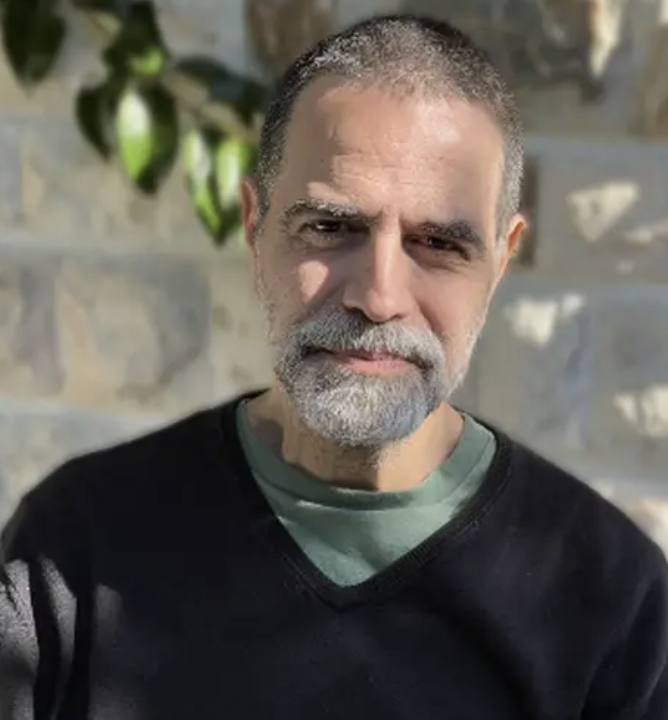

As a psychodynamic psychotherapist working in English, Greek, and French, I’ve observed how these shifts can open up new possibilities—or reveal hidden conflicts—in therapy. For multilingual clients, language is never just a tool for communication. It is a map of memory, identity, and feeling.

The languages we inhabit

Our first language — often called our mother tongue — is tied to early relationships and the emotional atmosphere of childhood. The words we first heard from our parents or caregivers carry a unique charge. They are the language of comfort, fear, belonging, or shame.

When people learn new languages later in life, those words often feel less emotionally loaded. This can be helpful — speaking about something painful in a second language can offer distance. But it can also make feelings harder to access.

I’ve worked with clients who could speak fluently about grief in English, but only felt the weight of it when they allowed themselves to use their native language. Others found it easier to discuss intimate or taboo subjects in English because it felt slightly removed from the critical voices of home.

Why we switch languages in therapy

Language shifts in therapy are rarely random. Often, they reflect something significant. A client might switch to a second language when a subject feels too close for comfort. Another might slip into the mother tongue when they want to feel truly seen.

I once worked with a man — let’s call him Nikos — who had lived in the UK for many years but grew up in Greece. In our early sessions, he spoke exclusively in English, describing his life with a steady calm. He talked about his professional achievements, a recent breakup, and a sense that “nothing feels real.”

Months into our work, he began to use Greek when he spoke about childhood memories. One day, as he described his father’s sudden death, he paused and then said simply in Greek: Den ipirhe kanenas — “There was no one.”

In that moment, his voice changed. The words seemed to carry an emotional weight that English couldn’t hold. It was as though the child part of him had found its language. From then on, he would sometimes move between English and Greek as he explored feelings of fear or abandonment. Over time, he noticed that his language choice mirrored how close he felt to those experiences.

One self, many voices

Some people worry that switching languages means they are fragmented or inconsistent. In reality, these shifts often reveal the richness and complexity of identity. Each language can evoke a different “self,” shaped by history, culture, and relationship.

In therapy, this can become a creative process. Clients learn to recognise which parts of themselves are speaking — and which parts have been silent. The goal is not to choose one language over another, but to allow all these voices to have space.

The power and pain of the mother tongue

For many, the mother tongue is the language of attachment. It can feel comforting to return to it —but it can also be the language in which early wounds were first felt.

Speaking about trauma in the language it was experienced can be intensely powerful. Some clients find this too much at first. Others find that it is the only way to tell the story fully.

In my experience, there is no right or wrong approach. What matters is allowing the client to lead — to choose when to stay in the familiar language and when to step back into a safer distance.

Why this matters

If you are multilingual and considering therapy, know that language is part of what you bring into the room. Your words carry the imprint of your life. Switching languages doesn’t mean you are being inconsistent — it means you are in touch with different parts of yourself.

For therapists, being curious about language can open up new understanding. Rather than focusing only on what is said, we can also pay attention to how and in which language it arrives.

Finding our words

Therapy helps people find the words for what they have carried alone. For some, those words come in English. For others, in Greek, French, or any other language woven into their story.

What matters is not perfect fluency, but the courage to speak — and the possibility of being heard.