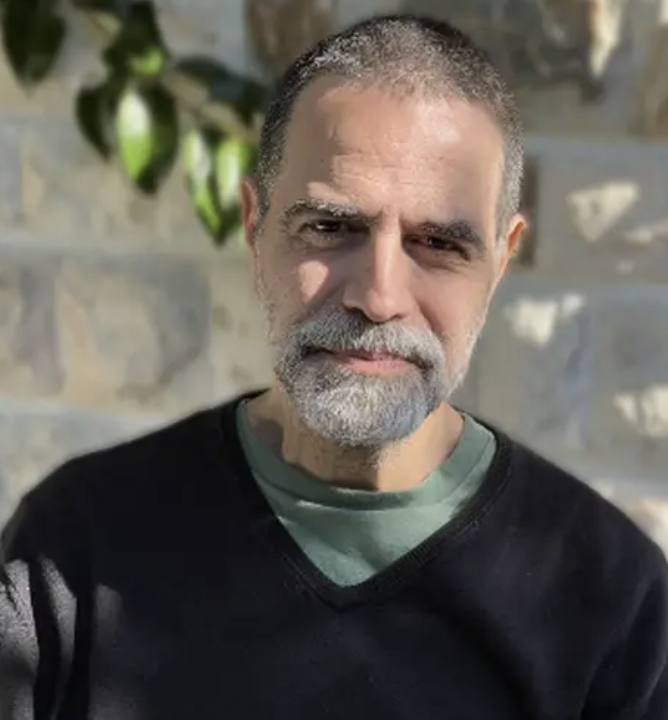

Ari Sotiriou is an online psychotherapist

What attracted you to become a therapist?

Long before I trained as a therapist, I found myself drawn to people’s stories—especially the parts that remain unspoken. I had a career in the electronics industry before retraining, but I always had a strong pull towards understanding emotional life and unconscious motivation. Eventually, I could no longer ignore the call to work more meaningfully with people’s inner worlds.

Where did you train?

I trained at WPF Therapy and completed my qualifications through Roehampton University, where I earned both a Postgraduate Diploma and an MA in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy.

Can you tell us about the type of therapy you practise?

I practise psychodynamic psychotherapy, a form of talking therapy that explores how early relationships, past experiences, and unconscious processes influence our present feelings, behaviour, and difficulties. I work collaboratively with clients to make sense of patterns that repeat in their lives and relationships—often outside of awareness.

This approach is well suited to people who want to deepen their understanding of themselves, especially when short-term solutions haven’t brought lasting relief. I was drawn to this tradition because it honours complexity and offers space for emotional truth to emerge over time.

How does psychodynamic therapy help with symptoms of anxiety?

Rather than treating anxiety as something to be eliminated, we explore what the anxiety might be expressing or protecting. Psychodynamic therapy can help clients understand the deeper roots of their distress—often linked to internal conflict, unmet needs, or past losses.

As insight develops, people frequently find that their symptoms begin to shift—not because we’ve “solved” them, but because they’re no longer carrying the same unconscious weight.

What sort of people do you usually see?

I work with adults of all ages, both individuals and couples. Many of my clients are professionals or creatives navigating complex inner lives—struggles with relationships, identity, trauma, loss, or questions of meaning.

In couples work, I often support partners in rebuilding communication, trust, and intimacy.

Have you noticed any recent mental health trends or wider changes in attitude?

There’s a growing willingness to talk about therapy openly, which is encouraging. At the same time, digital therapy platforms have changed how people access support. This has made therapy more available, but I also see concerns about how therapy is being shaped by algorithms, convenience, and performance metrics. There’s still work to be done in preserving the depth and integrity of the therapeutic relationship.

What do you like about being a therapist?

I feel incredibly privileged to accompany people on their journeys—especially when they begin to speak about things they’ve never shared before. There’s a quiet kind of bravery in therapy, and bearing witness to it is deeply meaningful.

What is less pleasant?

There are times when therapy feels raw and uncertain—when progress is slow or painful. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it can be emotionally demanding.

The solitude of private practice can also be a challenge, which is why I value peer supervision and connection with colleagues.

How long have you been with Welldoing and what do you think of us?

I was a member of Welldoing from 2018 for a number of years and have recently rejoined. I’ve always appreciated the thoughtful and well-curated nature of the directory, and the sense of community it fosters among therapists. I especially value the opportunities for CPD and peer support.

What books have been important to you in terms of your professional and personal development?

There are so many. Donald Winnicott’s Playing and Reality and Christopher Bollas’s The Shadow of the Object were transformative for me in terms of understanding how early experience shapes the psyche. I also admire Susie Orbach’s writing for how it bridges clinical insight and social context.

For clients, I sometimes recommend Lost Connections by Johann Hari for a broader view of depression, or The State of Affairs by Esther Perel when working with couples. But always carefully—books should support therapy, not replace it.

What do you do for your own mental health?

Living in the foothills of the Pyrenees with my partner and four dogs helps enormously. I walk daily, write regularly, and remain in supervision and peer discussion. I’ve also been in therapy myself for many years, which continues to be a source of support and growth.

You are a therapist in South West France and online. What can you share with us about seeing clients in this area?

I split my time between the UK and South West France, where I live near the Pyrenees close to the Spanish border. Most of my clients are online—some are expatriates like myself, others are based in the UK or internationally. Working across borders invites a sensitivity to place, language, and cultural identity, all of which can become part of the therapeutic exploration.

What’s your consultation room like?

My online consulting room is quiet, private, and warm. I aim to create a space that feels containing, even across a screen. There’s always a mug of tea within reach, and occasionally a sleeping dog just out of frame.

What do you wish people knew about therapy?

That it isn’t about fixing you. Therapy is a space where things don’t have to be solved immediately or tied up neatly. It’s a place to feel, think, remember—and to discover, over time, that something new might become possible.

What did you learn about yourself in therapy?

That much of what we carry is not fully known until we dare to speak it in another’s presence. Therapy helped me accept the parts of myself I once felt I had to hide. That has been both painful and liberating.