Last year, before embarking on a four-day hike on Heaphy Track on the South Island of New Zealand, my boyfriend surprised me by taking me to Mariua Springs mountain spa.

We soaked in the hot springs, walked around in bathrobes, had cocktails and dinner in the resort, slept like babies, and early the next morning, just after sunrise, we went to the Japanese bathhouse. It was quiet and peaceful, with sunlight streaming in, and no one else around.

We bathed in the pool for a few minutes and then spontaneously moved so that we were leaning back-to-back against each other. The pool was a little too deep to sit down in, and I positioned myself somewhat like a ballerina doing a deep curtsey: arms outstretched, head bowed, with one leg crossed under me and most of my weight on the other foot. It sounds uncomfortable but it wasn’t, as the water was supporting me.

My boyfriend leaned back so that his head was resting on the back of my neck and he was slightly reclining. We stayed like that, completely still and without speaking, for over 10 minutes, only moving when other people started drifting into the bathhouse. Later, he said, 'It felt as though our nervous systems were connected'.

That comment eventually led me on a deep dive into interpersonal neurobiology, a term that I have only recently come across. (1)

What is interpersonal neurobiology?

Interpersonal neurobiology was developed in the 1990s by Dr. Daniel J. Siegel, now Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine. This interdisciplinary field draws from research into emotions, cognition, neuroscience, evolution, anthropology, sociology, comparative anatomy and developmental psychology. It allows for a deeper and more expanded understanding of the brain, the mind, and human relationships.

It should come as no surprise to learn that what we say and do can affect others at a deep level — and vice versa. We all experience that reality every day and probably take such an extraordinary thing for granted. We humans, through our brains, seek to self-regulate and regulate those around us. This is known as sociostasis.

We know what to say and do to soothe our children. We know which toes will hurt, so to speak, if we step on them when we are arguing with a spouse or partner. We know that a hug or a compliment from someone we love goes a long way, making us feel secure, or inspiring us.

We can join a crowd and get caught up in the energy and the vibe — whether listening to music at an outdoor concert, attending an ice hockey game or a religious ceremony, or taking part in a protest march or a Black Friday shopping spree.

We have individual brains that also function as social organs, wired to be part of a family, a crowd, a tribe, a group, a throng, a clan, a herd.

We know the rules in a group: there are unspoken rules for how to behave whether at a PTA meeting, in the supermarket, at a football game or at a wedding or funeral. We cooperate, we accept or reject, we judge, we are altruistic or selfish, we consider pros and cons.

There are behaviours that are acceptable and normal, and others that are outside the agreed parameters and are frowned upon or laughed at. We have codes of ethics, rules, and regulations. Some behaviours are punishable by law. Language allows us to develop effective tools of social control. We have police forces and other professionals to keep an eye on us and enforce good citizenship.

These moral and legal codes differ between cultures and societies and may lead to different expectations, as well as misunderstandings, violence, and war. We may experience (sometimes conflicting) loyalties at multiple levels as we grapple with meeting our own needs and the needs of those with whom we are allied.

Different levels of communication

Communication within groups and between people occurs at multiple levels and happens all around us all at the same time. We process cues, quickly and unconsciously, that tell us who is in our group or tribe and who is an outsider.

Evolutionary research shows that compared to our closest primate relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, humans have evolved to be much less aggressive to members of our tribe or in-group, and more likely to go to war against outsiders.(2)

Our languages, and the words that we speak, are delivered in a huge variety of tones of voice, accents and dialects. We may use sarcasm or humour that alters their perceived meaning and is intended to be understood only by a select “in-group.”

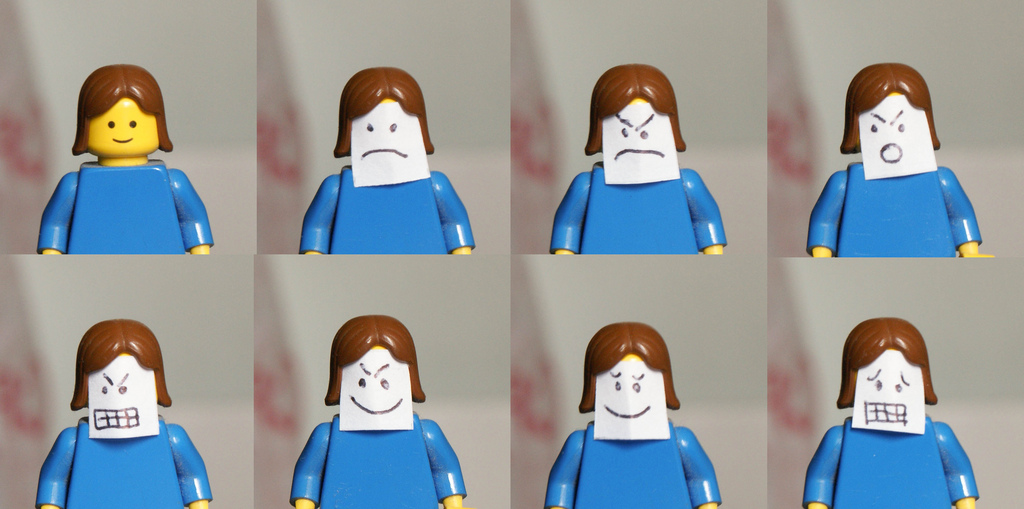

Visual input, or what we observe with our own eyes, includes what is conveyed by clothing, hair styles, skin colour, piercings, tattoos, jewellery, colours, shoes, accessories, facial expressions, micro expressions, eye and eyebrow movements, blinking, laughter, tears, sighs, groans, gestures, touch, personal space, eye contact, the set of the jaw, how we walk, the position and movement of arms or legs, or aggressive behaviours.

The non-verbal messages say: I am powerful. I am submissive. I am scared. I am invisible. I have money. I am one of you. I am not one of you. I am homeless. I like this kind of music. I like this kind of sexual partner. I don’t like myself. I don’t like you. I am depressed. I am happy. We’re in this together. I am insane. I will hurt you. I will take care of you. I am old. I am a child.

Cues alert us to whether someone in the group is ill or infectious with something potentially life-threatening and therefore to be avoided e.g. skin rashes, runny noses, open sores, coughing or sneezing, blood, vomit, holes, or missing or malfunctioning body parts. These all scare us on some level.

We signal to others by universal facial expressions like disgust, or a sudden intake of breath, a laugh, or a scream. We blush or stick out our tongues. We kiss. We point, clap, whistle, and shout. We stamp our feet and chant or sing. We may start to run without even knowing what we are running away from or towards. Fear takes over, or laughter, anger or hatred.

So how do our social brains do, perceive, and process all of these things?

As humans, we interface with other people, and when we receive and transmit information verbally and non-verbally, this is analogous to the transmission of energy and information across the synapses (junctions) between neurons (nerve cells). This social synapse allows us to link our brains to others’ brains.

When we are functioning well, in a state of well-being, the various parts of our brain function as a balanced and harmonious whole. This is called integration.

Our mirror neurons fire off when we watch or witness someone’s actions, as though we ourselves were performing them. These enable us to not only understand another’s intentions, facial expression, tone of voice, and therefore emotions, but to feel in the body what it is like to be engaged in those behaviours. This is a factor that allows us to learn by watching, mimicking or copying another person. It also allows for the development of theory of mind — the recognition that other people have minds and can think and act with intent, just as we can.

Interestingly, if something interferes with our mirror neurons, like an injury that paralyses facial muscles, or even botox for cosmetic purposes, our ability to discern the meaning of facial expressions in others is affected.(3, 4)

We have attachment systems, with mechanisms and chemicals for bonding with our caregivers, family members, and intimate partners — endorphins, oxytocin, vasopressin, dopamine, and serotonin.

We can observe the mind and the workings of the mind with a detached awareness that can be cultivated through practices like meditation. We all have the ability to do this — to not only recognise that we know something, but to recognise that we are the knower, a reflective and observing self.

The definition of mind in interpersonal neurobiology is very specific i.e. the mind is not simply the result of neural activity in a single brain but describes what emerges through connections to others, in relationships, within the context of culture or society. The mind is therefore a product of not just the individual’s nervous system, but the extended nervous system created by the interaction of two or more people.

So, next time you put your arm around a friend, pat a buddy on the back after a game, kiss your lover, or calm down an anxious child, notice what happens, in you and in them. Perhaps you are an amygdala whisperer (5)… and you didn’t even know it!

References

(1) Cozolino, L. (2022), Interpersonal Neurobiology Essentials, W. W. Norton & Company.

(2) Wrangham, R. (2022), The Goodness Paradox: The Strange Relationship Between Virtue and Violence in Human Evolution, Pantheon.

(3) Birch-Hurst, K., Rychlowska, M., Lewis, M. B., & Vanderwert, R. E. (2022). Altering facial movements abolishes neural mirroring of facial expressions. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 22(2), 316-327.

Hennenlotter, A., et al. (2009). Botulinum toxin-induced facial muscle paralysis affects amygdala responses to the perception of emotional expressions: preliminary findings. Biology of Mood & Anxiety Disorders, 4(11).

(5) Cozolino, L. (2015). Why therapy works: Using our minds to change our brains (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). W. W. Norton & Company.