May I begin by saying that if you are reading this because you have recently lost your baby, I'm so sorry. Although nobody can understand the pain you're feeling, because each person's grief is unique, I have some idea from my personal and professional experience.

Miscarriage and stillbirth: the numbers

The NHS estimates that 1 in 8 pregnancies end in miscarriage during the first 23 weeks of pregnancy , although many of these are so early that the woman is not aware that she is pregnant. Every week in the UK, on average 47 babies are stillborn 24 weeks to full-term . That equates to four stillbirths for every 1000 babies born.

In spite of miscarriages being so common, you and your partner can feel a strong sense of loss and grief, particularly if the pregnancy was planned and the baby eagerly anticipated. Parents often suffer in silence, an unshared grief unrecognised by society. If you experience multiple miscarriages, anxiety and despair adds to your grief.

I have supported women after quite early miscarriages. They had bonded with their baby and their grief was as intense as any other bereavement, which too brings guilt and trauma. It can help to name your baby and to choose some kind of memorial. The charity SANDS Stillborn And Neonatal Death Charity has memorial gardens in many towns, where parents can place flowers and leave a memorial pebble painted with their baby's name. The charity also hosts a virtual garden online. The are other virtual memorials for unborn babies you can find online.

The time after the stillbirth

Whether your baby's heart stopped days or hours before the birth, or during the birth, either will be devastating. Many maternity hospitals have specially trained staff and a bereavement suite to help parents through this sad time. You will have the opportunity to spend time with your baby until you are ready to say goodbye. You will be able to take photographs, hand and footprints and perhaps a lock of hair. Whilst at first these may be hard to look at, in time they can become comfort.

Finding out what happened

Nearly everyone's grief is softened by understanding exactly what happened and in finding a reason for the loss. Intense grief lingers when no causes are found. Make good use of PALS Patient Liaison and Advice Service which all NHS hospitals have. The service exists to work for you and many of my clients have found the outcome helpful.

One of the most difficult choices you will have to make as a couple, is whether your baby should have a post-mortem examination. The choice is yours and most hospitals use a sensitive and carefully worded simple consent form written by the charity SANDS. A post-mortem can find out what went wrong and keep safe any babies you may have in future. Research from post-mortems may prevent the tragedy happening to other parents.

You can choose between a limited post-mortem, which includes a careful examination of your baby and of the placenta, or a full post-mortem usually by a paediatric pathologist. You will be asked if some of your baby's tissue can be prepared as microscope slides. A discussion with hospital consultants afterwards will help you decide on and plan future pregnancies. Following a late miscarriage or stillbirth, obstetricians will go to great lengths to keep you and your baby safe in future.

Should you believe there was negligence on the part of the hospital, then understandably you will want to get justice for your baby. The SANDS website has sensitive advice to offer on this.

Going home to an empty nursery

If this is your first baby, you will be going home to an empty house with a new nursery and cot. Decide what you are going to do. Remember that some of those precious objects can be added to your memory box. There are no right or wrong answers for what you should do with the cot and the baby clothes, or whether you should redecorate the room. Every couple's grief is unique, and it is your decision to make together.

Dealing with the emotions

Your natural grief may be weighed down with anger and guilt. Seek out friends, family and perhaps professionals who will let you share your emotions without trying to silence you, minimise or explain away what you feel.

Dealing with the trauma

If you feel traumatised by events it can help to discuss your experience with each other, with family members and with a specialist counsellor or volunteer. Talking helps make sense of what happened and reduces the possibility of your trauma becoming a serious condition. In the unlikely event that talking is not enough, ask your doctor if you should be referred to a specialist psychological service. There are counsellors and therapists on welldoing.org who specialise in miscarriage and pregnancy; find them by using the questionnaire option here.

Do men and women grieve differently?

Experts have described two ways of grieving. Instrumental grief involves being practical, trying to solve problems and trying to get on with things. Intuitive grief is far more emotional, letting the tears flow and following feelings. Instrumental grief is usually assigned to men, and intuitive grief to women. It's a false and binary distinction, and unhelpful because each gender may try to conform to the expected norm. I have known mothers to cope better than fathers after losing a child.

What does appear to be common, is for the father to protect the mother by trying to be strong and not showing their grief, at least in the early months of the loss. That may be just as common in same-sex female couples, with the birth mother being protected by a 'strong' partner. Whilst there may be differences, each person and each couple should be recognised for their uniqueness. If you are tempted to support your partner by bottling up your own needs, in the long run its unlikely to do either of you any good and risks stressing your relationship. Open and honest communication is the best way of supporting each other.

Talk and listen to your children

Explain carefully what happened in words appropriate to their age. Even before they can talk, children will pick up on their parents' sadness and stress and may feel unsafe. Extra cuddles and soothing sounds will help. Children younger than three won't understand what it means to die. Children from four to six know what the word means but don't understand that death is irreversible. Some of their questions will be difficult and you'll probably need to go over it many times. Be honest in answering their questions and listen to what they understand and how they are feeling. It's OK to show you are upset, it's how they learn about emotions. Try not to avoid the words 'dead' or 'died'. To talk about sleeping and not waking up can frighten children about sleeping. If you talk about heaven, stars or angels, you will need to explain that their brother and sister can never come back. It's hard - I know because I had to explain her little brother's death to my daughter when she was three years old. The charity Winston's Wish can help you help your children.

Seeking professional support

The charity SANDS has a helpline and runs support groups. If you decide to see a private counsellor, make sure that they are experienced in this field. You can choose to go as a couple or individually. You may find that the counsellor who sees you as a couple would not go on to see just one of you, and some counsellors would not see both partners separately, you would each need a separate counsellor. Your counsellor will explain why this is.

There are different kinds of groups, and what you will find helpful will depend on your needs, your personality and the skill of those running the group. Drop-in, social groups over tea and biscuits give you the opportunity to meet others who have had the similar experiences and can offer much needed company. Open-ended support groups have a facilitator and sometimes guest speakers, and you join and leave when you feel ready. A closed group is facilitated, but everyone joins at the same time for a set period. No kind of group suits everyone. A closed group can end before you're ready. A social group may not give you the space to share deep emotions. One potential problem with any open group is that people may be at very different places in their grief journey. New members can feel left out and longstanding members can be affected by stories of new losses. If you are seeking a group, don't be afraid to ask how it is run and the experience of the facilitators. If you find it's not for you, it won't be your fault.

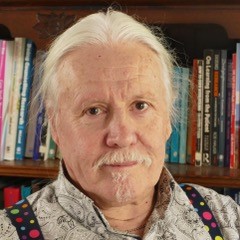

Dr John Wilson is a counsellor who has specialised in loss and grief for over 20 years. His first son Paul died from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome aged 14 months. He is the author of The Plain Guide to Grief: