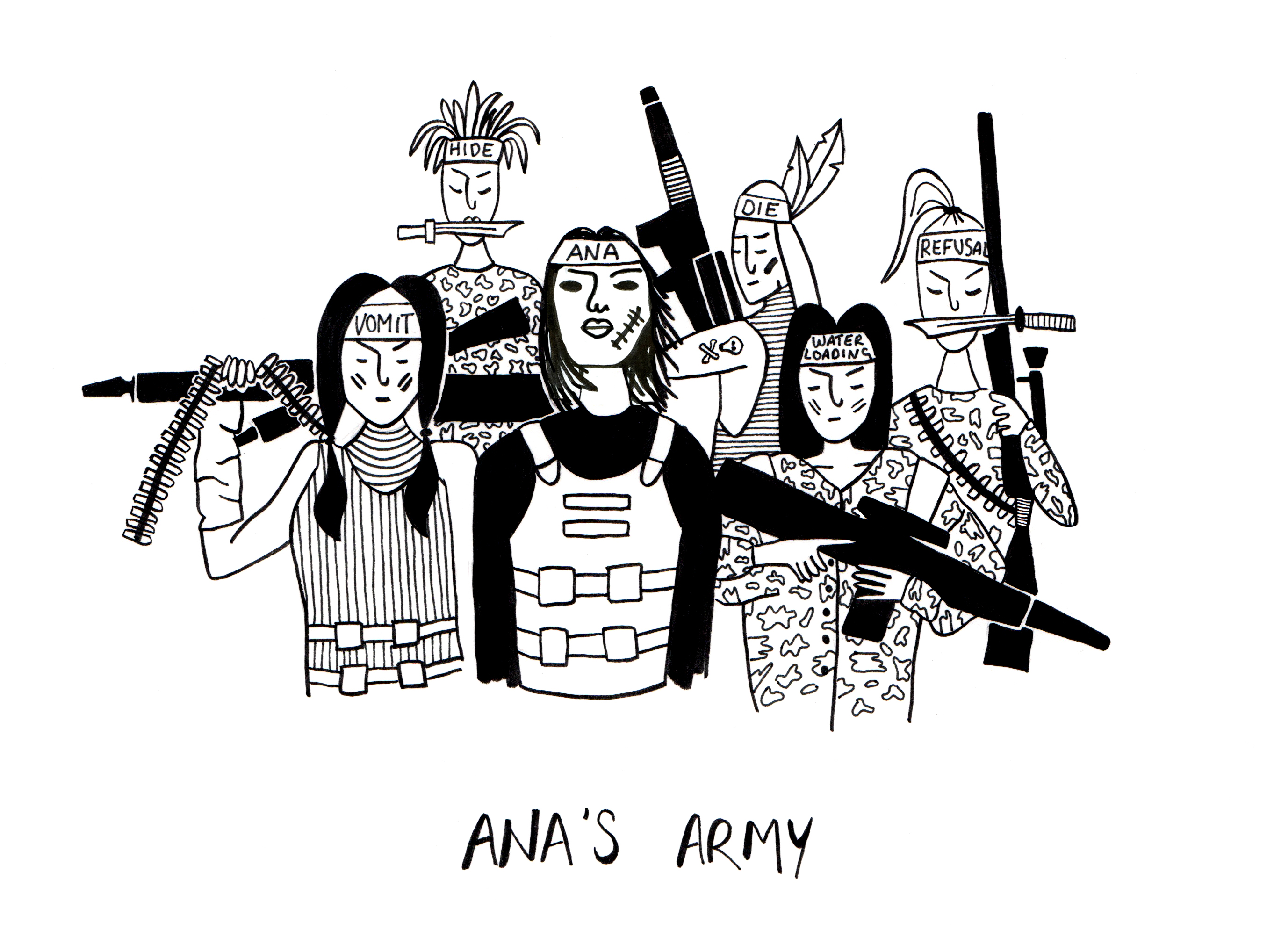

Between 2012 and 2018, we had an unwelcome visitor to stay in our house. We called her Ana, an 'affectionate' name for anorexia nervosa, the most lethal of all mental health illnesses. Ana was 'visiting' our daughter, Emily, who was just 16 at the time. During the course of those six years we were to discover what a formidable enemy Ana was. She was cunning and cruel, devious and dishonest. She taught Emily every trick in the book called 'How to lose weight'. Hiding food, regurgitating it after meals, taking laxatives to get rid of unwanted calories, or simply refusing point blank to eat.

My wife, Mel, and I were complete amateurs confronted by a consummate professional who was driven by a single-minded objective: kill our daughter.

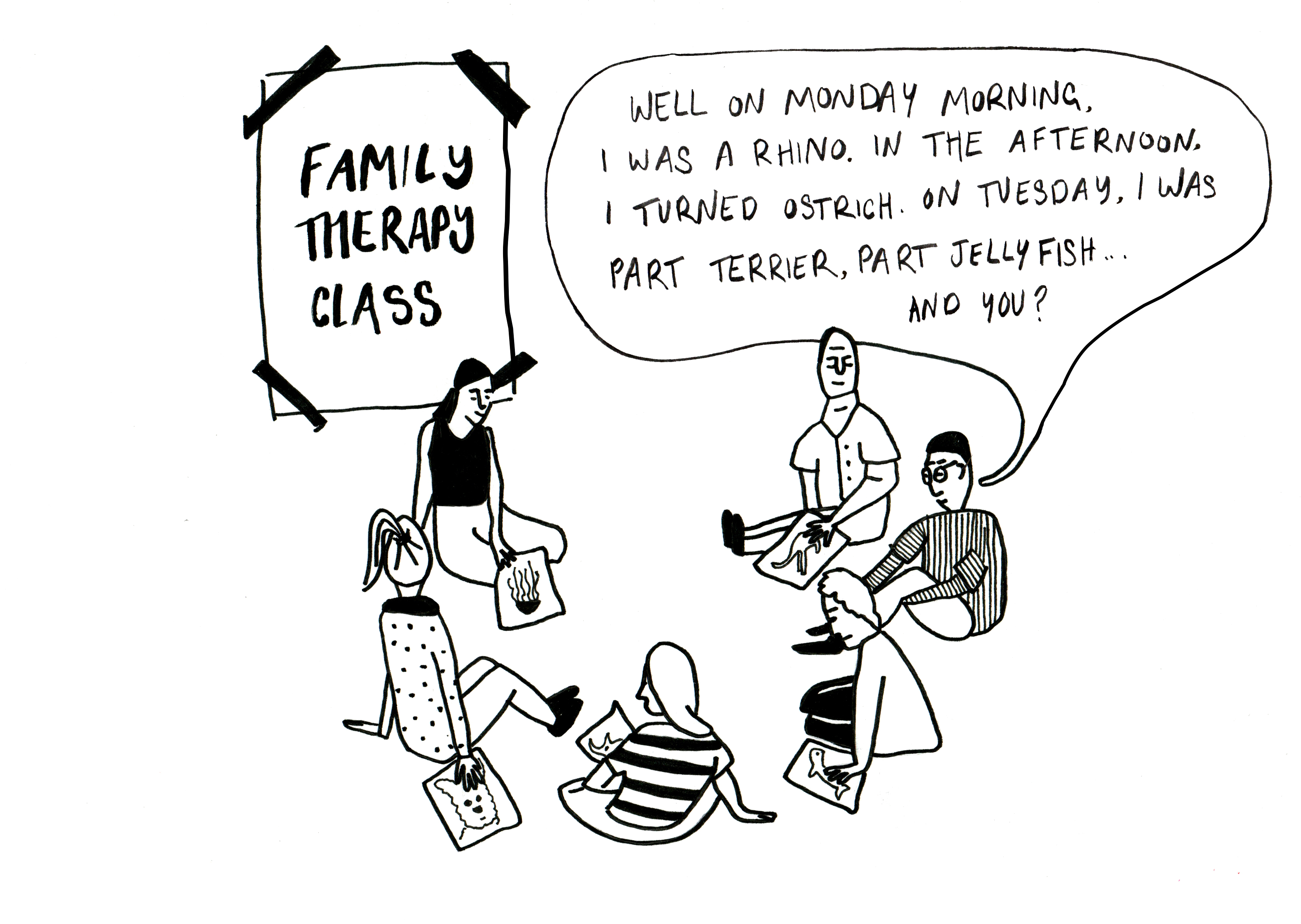

As parents, we were eventually given support and guidance by one of the eating disorders clinics on how to deal with the illness. We needed reinforcements because we were no longer able to cope on our own. A well-renowned psychologist in the field of eating disorders, Dr Janet Treasure, had developed a powerful analogy based on different animals to help parents deal with their disordered children when they were at home.

Her animal analogy was widely embraced in the world of therapy because the parent was often the one stakeholder with most influence on the recovery process of the sufferer. The better skilled they were as 'counsellors', 'therapists', and supporters, the better chances their children had of making a recovery.

Mel and I had failed miserably during the first six months of the illness, so we were thankful for any help we could get.

Even from a bunch of random animals.

Here is a short summary of the animals and the parental behaviours they represent, both unhelpful and helpful:

Jellyfish

They show too much emotion and therefore exhibit too little control over proceedings. They are unable to hide their distress and anger at what is happening around them. Stings occur because their uncontrolled and raw emotions are often mirrored by outbursts from the sufferer themselves.

Ostriches

They exhibit an avoidance of emotion. They live in denial because they find it too hard to cope with what is going on right in front of them. They prefer to bury their head in the sand and pretend nothing is happening. As a result, the sufferer sees the carer as uncaring and feels unloved. Their self-esteem ebbs away further still.

Kangaroos

They are the complete opposite to Ostriches. They treat the sufferer with kid gloves, mollycoddle them, and let them jump into the kangaroo pouch at every opportunity to avoid any difficult conversations. This cocoon-like existence prevents the child from tackling the illness and addressing the challenges they are faced with.

Rhinos

They use brute force, logic, and strong arguments to try and convince the sufferer their way is the right way. This often leads to confrontation and only serves to strengthen Ana's resolve further still. If you start hurling grenades her way, she summons the rest of her army to return fire with even heavier artillery.

Terriers

Their chief attribute is never-ending persistence. They have the same objective as the Rhino but try to achieve this in a cajoling, nagging, irritating kind of way. After a while, the sufferer tunes out, blocks out the noise and stops listening. Ana learns to bark back even more loudly and more annoyingly, and nothing is achieved.

The two role model animals are the Dolphin and the St. Bernard Dog. They demonstrate the right behaviours when tackling anorexia, ones proven to help rather than hinder recovery.

Dolphins

Their strategy is to use just enough caring and control to help nudge the sufferer towards recovery. Imagine your child is out at sea, wearing a life vest and the life vest is Ana. She is struggling and suffering but she is afloat and without the life vest/Ana, she fears she will drown. The Dolphin persuades the sufferer to take off their life vest and start swimming back towards the shore. They promise to remain by their side, encouraging, supporting, loving, demonstrating that life without Ana is both possible and preferable.

St Bernard

They provide compassion as well as consistency. They try to instil the hope in your loved one that the situation can and will change. They are forever the optimist and show nothing but kindness and love. They remain unflappable even in times of trouble, and most important of all, they never ever leave your side.

The theory underpinning the animal analogy was spot on, and the theorist in me loved the thinking. It couldn't be faulted, and Mel and I tried our best to be Dolphins and St Bernards. We would leave those sessions positively barking and making sweet squeaking dolphin noises on our way home. We were desperate to kick our Jellyfish, Ostrich, Kangaroo, Rhino, and Terrier tendencies into touch. However, when the pressure was on, we inevitably reverted back to these destructive traits in some form or other. We knew full well we had to be either Dolphins or St Bernards but when your daughter is hiding stuff, lying to you, being rude to you, and throwing her life away in front of your very eyes, it's hard to translate theory into practice.

Like any new habit, Mel and I really had to work hard to integrate the new behaviours into the way in which we dealt with our daughter. We would become coaches to one another, praising and encouraging one another when Dolphin and St Bernard behaviours were successfully demonstrated. And reminding each other about what we had been taught when the pressure was on at home and we might revert back to unhelpful Rhino and Terrier behaviours. But it was hard not slip back into bad habits.

However, as our daughter inched her way towards recovery in 2018 and 2019, the good habits became more engrained and the effect that this had on Emily was a very positive one. They helped her turn the corner.

Applying the approach in other walks of life

Using Janet Treasure's animals became a vital part of our weaponry in the fight against anorexia nervosa. Without it, we really do believe that our daughter's recovery would have been delayed.

I wonder whether the approach could also play a useful role in dealing with other difficult people and situations? Could it be employed when dealing with an unruly teenager making that difficult and painful transition between child and adult? Could it be used by managers in the business world trying to extract the best out of their teams? Or on the sporting field where coaches want to achieve the same. The answer is probably 'yes' in all three cases, because ultimately what underpins the approach is a positive psychology, relevant to any kind of human relationship. The underlying characteristics and traits of a Dolphin and St. Bernard are so powerful because at their core, they are meeting the needs of the person who needs help.

And if a parent, boss at work or sporting coach can do that, they are more likely to get the result they are looking for as well.

Win: Win.

Mark Simmonds' book, Breakdown and Repair talks candidly about his own experiences with mental ill health both as a sufferer and as a carer. Follow Mark on Instagram @mentalhealthmark