The Shipman Files: What Motivated Harold Shipman, and How Did He Get Away With It?

-

Dr Harold Shipman killed at least 215 patients and maintained his innocence until the day he died himself

-

Psychotherapist Ajay Khandelwal reviews recent BBC documentary The Shipman Files

Cheering the NHS has become a national pastime in recent months. With very good reason we have projected a range of heroic qualities onto caring professionals. They can do no wrong, and should be provided with free beer and respect for life! It would seem extremely miserly not see them as wholly good! Most psychotherapeutic theories would feel uneasy about this understanding of human nature and human systems. Heroes exist in fairy tales and legends, the reality of everyday life is always much more complex and messy.

We often try and do one thing, and end up doing the very opposite. We set out on a conscious path, and the unconscious undoes it. We know that medics don’t always get things right. We know hospitals are good, but somehow we feel scared to go anywhere near them. A recent study by John Hopkins University found that 250,000 deaths occurred every year in the US to medical errors. This could be through amputation of the wrong limb, or administration of the wrong drug. Just like every other walk of life, health care, and the people who work within it, are a mixed bag, neither wholly good, or wholly bad, but somewhere is the middle. The social critic Ivan Illich coined the term iatrogenesis, referring to the harm medical interventions can have on individuals and societies. It has been estimated that up to 20 million people have been harmed worldwide through medical negligence of one form or another.

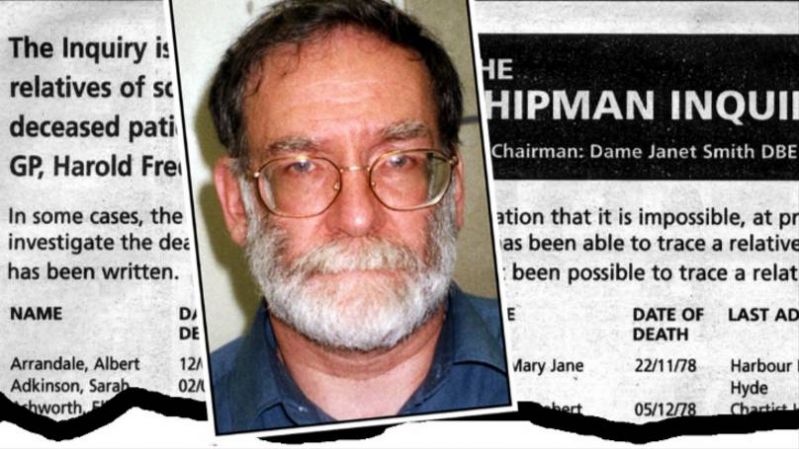

The world’s most prolific serial murderer: Mr Harold Shipman

As an antidote to our current, pandemic-induced, one-sided view point, it might be instructive to watch some TV. Mr Harold Shipman, the world’s most prolific serial killer, is the subject of the new three-part documentary on BBC2, the “Shipman Files.” Now Mr Shipman is clearly an extreme outlier, and the very opposite of the heroic medic narrative of the moment. Yet, this tragic story can be reviewed and revisited from many different angles in order to get an understanding of health care today. Film maker Chris Wilson’s focus is the story of the patients and their unsuspecting families, and he does a wonderful job in capturing their tender memories of their murdered family members. But what is striking is how much many of them loved Dr Shipman, and were completely taken in by him, due to his unwavering interest and attentiveness. Mr Shipman appeared to have the best medicine of all, a caring and empathetic bedside manner. Such attention is like gold dust in an overstretched and under resourced health system. Yet, we now know that he murdered at least 215 – mainly elderly women, but also some men and children.

An old fashioned family doctor

The early psychoanalytic pioneer and GP, Michael Balint, argued that it was important to spend lots of time with the patient, in order to understand their whole life story, and not just treat them for a specific symptom. Nowadays, the average doctor’s appointment in the UK is about six minutes and many patients feel short-changed. Patients have to book double appointments if they want to talk about more than one subject. Home visits are unheard of. Mr Shipman appeared to be cut from a different, generous, Balint-like cloth, a true healer from a bygone era. He would visit families at all times of day and night, and appeared to be especially interested in making home visits. Mr Wilson’s documentary gathers family testimonies that show he often dropped by unexpectedly to check up on his patients. By all appearances he was the archetypal family doctor of the collective imagination, dedicating himself to his patient’s welfare.

A millionaire's death

He provided elderly women with what was termed “a millionaire's death.” Most elderly people abhorred the idea of dying in an uncaring institution as a result of poverty. Most of Mr Shipman’s patients died, it appeared, peacefully at home, often from what he described on their death certificates as “old age.” This appeared to be fitting ending to a well-lived life. It chimed with something deep in the culture at the time, and appeared to be a fairy tale ending for all concerned. Family figures appeared able to bury any disquiet they had about healthy relatives dying for no particular reason. It was just taken for granted that old people could die suddenly. It was a tacit assumption that a good life was one where an old person, aged 70 or 80, should be grateful for a quiet death at home, even if they didn’t have pre-existing conditions or complications.

It was also because there was a culture of deference to authority figures, such as doctors, and police. In psychotherapeutic language we might say there was a strong and positive transference to such authority figures, who were considered to speak the truth. The level of deference to Mr Shipman, a middle class doctor, in a working class Northern town, was dramatically illustrated by Chris Wilson’s interviews with family members. Even after evidence of this wrong doing, many families rallied to his defence, unable to square their intimate experience of him.

Mr Shipman: mad, bad, or sad?

What I found rather strange about Chris Wilson’s documentary is that there was no attempt at all to understand Mr Shipman’s psychology. We know that he was very close to his mother who died aged 43, when Shipman was a teenager. We know that he saw his mother being administered morphine to manage her pain. Freud coined the phrase, “repetition compulsion”, to describe situations that we unconsciously recreate, in order to make sense of traumatic situations. Mr Shipman trained as a GP, became addicted to the pain killer pethidine, and then injected his patients with it. He appeared to have become addicted to killing his patients. Much of his life could be understood as replaying this tragic story in more and more compulsive and destructive ways.

The analyst Guggenbuhl-Craig, in his book, Power in the Helping Professions, argues that helping professionals can fall into their own shadow. Mr Shipman, rather like Jekyll and Hyde, appeared to have – through his dependence on pethidine – fallen completely into his own shadow. He appeared to form deep and caring relationships with his patients, but this was all a charade, in service to his need to kill. There were only a few people that could see Mr Shipman’s shadow, often individuals with limited cultural and social power, such as the undertaker, who noticed that all the bodies appeared to be in similar poses. His concerns were dismissed by an earlier police investigation. It appears that most people had their vision obscured, as part of a collective shadow, which failed to truly value the lives of older Northern working class women.

Will there be another Shipman?

Mr Shipman maintained his innocence until the end. He even set up an informal surgery and provided medical advice to fellow inmates when he was in prison. It was only when he was put into solitary confinement that he committed suicide by hanging himself. Surely, such a tragedy could never occur again? Well, yes and no. I think it’s unlikely we’ll ever see a serial killer get away with what Shipman did. However, in some ways Mr Shipman was a canary in the coalmine, in terms of changes in the health system. In the US drug companies have advertised pain killers direct to the public and paid doctors lavishly to over prescribe them. Pill mills have been set up in poor rural towns, resulting in chronic addiction to prescribed medication and fatalities. In some cases doctors have become addicted to pain killers as well as patients. In the UK, deaths from prescribed pain killers now exceed deaths from recreational drug use. There are over 100,000 prescriptions for pain killers written every day. There are five related deaths each day, in the UK. We can be fairly confident that there will never be another Mr Shipman in the UK, but as we medicalise pain, and turn to powerful drugs to treat it, we are appear to be sleep walking into another medical catastrophe.

Psychotherapy is another way of dealing with pain, both physical and psychic. Ivan Illich, a big critic of the creeping medicalisation of everyday life, would surely have argued that one of the best ways of dealing with pain is through talking and giving each other attention, professionally, or otherwise. However, this isn’t very interesting to big pharma. It can’t easily be replicated, scaled or commodified (although there have been attempts!).

Ajay Khandelwal is a verified welldoing.org psychotherapist in London and online