Does Hoarding Relate to Childhood Experiences?

-

Hoarding disorder is thought to affect 2.5-5% of the population; it's characterised by a need to acquire and keep hold of objects

-

Stuart Large talks to researcher Jessica Barton about how hoarding disorder and childhood experiences may relate

-

You can find help for hoarding disorder on the welldoing.org directory – use our questionnaire here

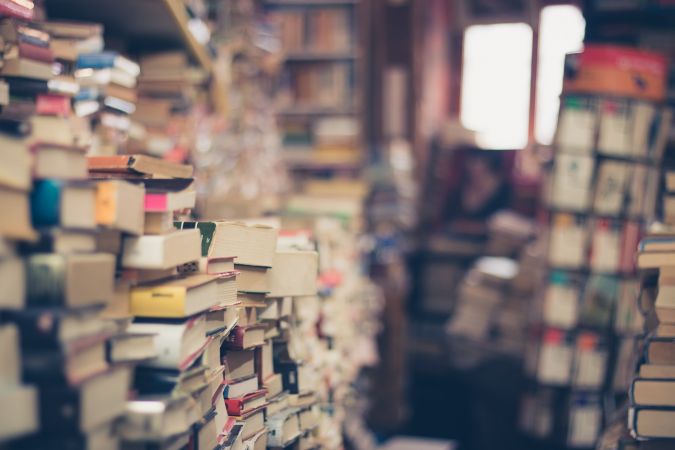

Hoarding is defined as 'the excessive acquisition of objects, persistent difficulty parting with possessions and the resultant build-up of clutter in the home’. It’s thought to affect between 2.5-5% of the UK population.

Hoarding disorder is a condition with a myriad of factors at the root cause. It is linked to practically all other mental health conditions in the sense that hoarding behaviours exist on a spectrum, which makes diagnosis tricky.

Over recent years, the amount of research into hoarding being commissioned has increased. One of those research studies has been conducted by Jessica Barton, trainee research psychologist at The Oxford Institute of Clinical Psychology Training and Research. The survey called for anyone in the UK with a significant hoarding problem, either with OCD or without mental health concerns (healthy control group) to respond.

I spoke to Jessica to understand hoarding further. '"There are three different beliefs someone holds that can drive this behaviour," she tells me. "First is a belief about avoiding harm – that something awful will happen if I don’t acquire this object – next, it’s a fear of material deprivation leading to someone feeling they are preventing themselves being deprived at some stage in the future, and thirdly, that an attachment to possessions may take the place of relationships with people." It’s the last of those that her work focuses on: trying to better understand parental bonds or attachment styles in early years and how these may affect someone's hoarding behaviour.

The survey showed that those with hoarding disorder and OCD were more likely to cite their experience of parenting as significantly less caring and emotionally comfortable compared to the healthy control group. Jessica goes on to explain: "attachment security is important, but it’s a general vulnerability factor for mental health conditions, not just those with a hoarding problem".

Hoarding is at times sensationalised in mainstream media; this could easily act as a barrier to sufferers seeking professional help, due to feelings of shame. Dr Lynne Drummond, known for her work on OCD, has published case studies on how the problem spirals out of control: in one severe case, filling the house and garage with paperwork and newspapers to satisfy the sufferer’s anxiety of losing ‘vital information'.

Despite the severity of the condition, It is reassuring to hear about the support and awareness training available our there. Heather Matuozzo is the founder of Cloud’s End, a Community Interest Company, providing 1-1 support directly to clients locally in Solihull and importantly delivering awareness training to East Sussex and Brighton & Hove Councils. "Knowledge around hoarding behaviours is the key: as soon as you understand why the behaviours might be happening, I think you come alongside the person, you are in their team."

Hoarding has been classified as a separate condition to that of OCD in recent years, despite having similar symptoms, so there are different pathways for support. If you know someone who thinks they might have a hoarding problem, you can get help and information from Cloud's End; you can also find therapists who are trained to work with hoarding disorder by using the welldoing.org questionnaire.

Watch my full interview here:

Stuart Large is a freelance writer covering mental health and creative arts - you can follow him on twitter @boyaboutsound