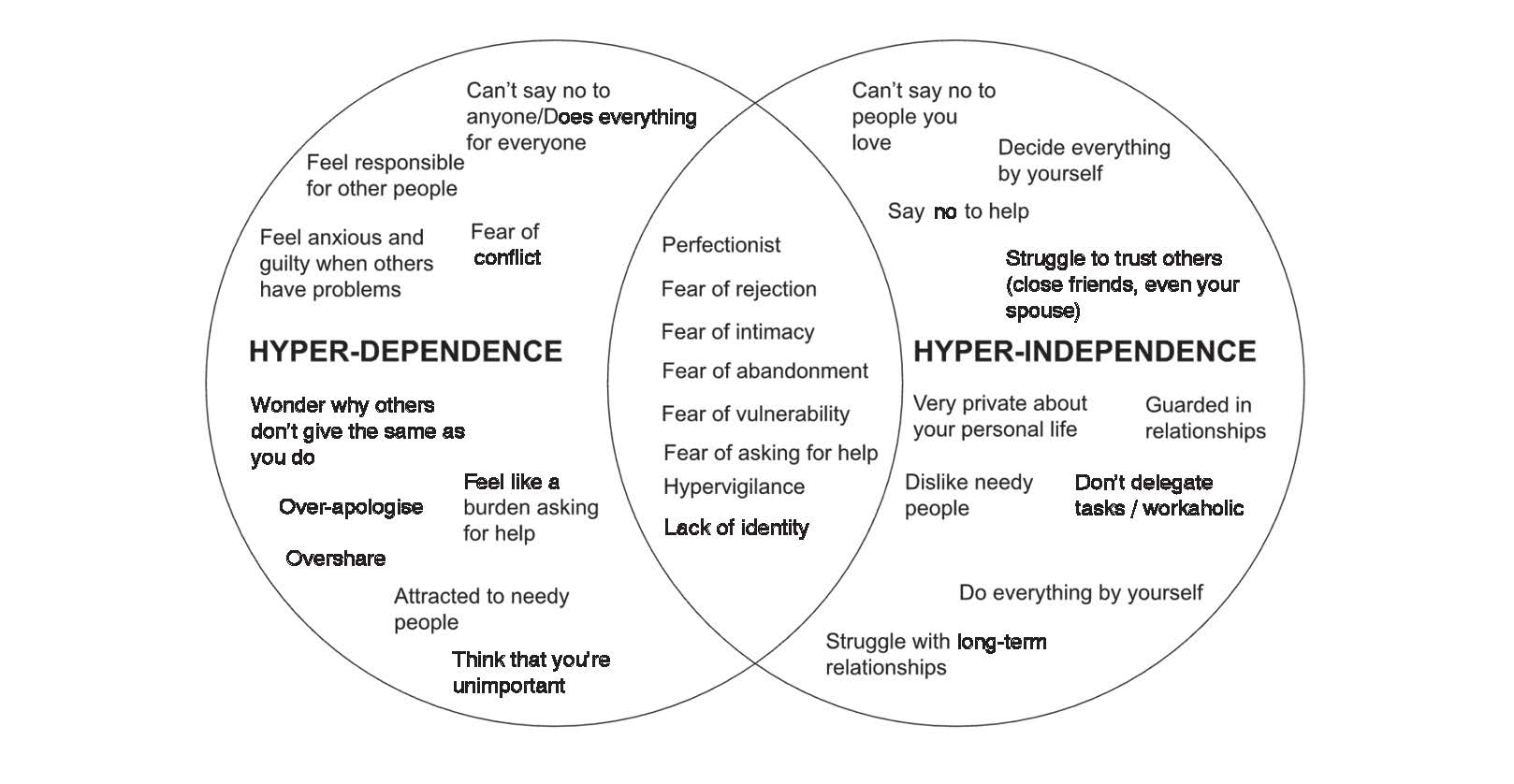

A multitude of wounds are created by the narcissistic parent, but ultimately they can be separated into two camps: hyper-dependent and hyper-independent. Most people think they fit into one or the other of these categories. However, those with restricted emotional growth typically develop both types, sometimes with one being more obvious than the other and sometimes alternating between the two in equal measure.

Toxic shame

The most important thing to remember is that ever one of these behaviours is rooted in shame - not loveable, not good enough, offering nothing of value to the world. Toxic shame can obliterate ones self-esteem in a heartbeat, with an overwhelming sense of self-distain that you are stupid, useless, pathetic, worthless, defective, despicable, fatally flawed.

When someone is in a toxic shame spiral, it can prevent from seeking comfort and support, instead they isolate themselves and hopeless and an overwhelming feeling of humiliation.

How shame takes root

In the narcissistic family system shame is weaponised from the moment the child is born. Babies are labelled as either "good" or "bad", as though the child's cries for food, comfort and being kept clean are an intentional attack on their parents parenting.

A toddler who knocks over a cup of juice is met with anger, irritation and comments on their clumsiness and how much work they've caused their parent. The four year old who doesn't want to share their sweets at the party is called selfish and mean. The eight year old who fails their spelling test is called lazy or stupid and told that they've disappointed their parent. The twelve year old who wants to go to the movies with their friend instead of their parent is accused of being hurtful and cold-hearted: "What's wrong with you? How could you do that to me? Where did I go wrong with you? What did I do to deserve a child like you?"

And it goes on: shame being drip-fed into a child via responses that tell them they are a perpetual disappointment to their parent, and never good enough. The child sees themselves through the lens of their parent, but the lens of the narcissistic parent is warped. It's broken and clouded and doesn't show the true picture and gives their child a view that shows them in the worst possible light. The child learns to believe they are inherently bad; they feel unwanted and start to feel intense shame about it.

Because the narcissistic parent relies so heavily on emotional and physical abandonment for control stonewalling, the silent treatment, anger, motivational empathy, slapping, hitting and other forms of physical abuse , their child becomes hypersensitive to rejection. And every time they are rejected, it's confirmation that they're not wanted, and the pain is devastating. Tangled up with shame, it creates the not good enough wound. Then, every time they encounter something that resembles rejection, it opens that would and pours salt on it.

The FOG: Fear, obligation and guilt

For anyone who grew up in a home where they were "walking on eggshells", they experienced a childhood in which emotional or physical safety wasn't consistent, stable and predictable, fear obligation and guilt FOG will be the dominant emotions controlling their behaviour and decision-making. The child's fear, obligation and guilt are weaponised against them to dominate and control them, forcing them to meet their narcissistic parents needs above their own.

In adulthood, the FOG descends, takes a hold and overwhelms the child of the narcissistic parent: the fear is their fear of rejection, of abandonment, of shame. Obligation is their sense that they must meet the needs of others above their own. And guilt is what they suffer when they do not and cannot meet those needs.

Hypervigilance

We hear many of our clients refer to themselves as empaths, however they are not empaths, there is no such thing, they are victims of abuse. They are have learned to anticipate another's behaviour in order to keep themselves safe, whether in adulthood or childhood, and therefore are hypervigilant.

Hypervigilance - born from prolonged exposure to threat or fear - is best explained as being perpetually on high alert, like a deer listening for a predator. Someone who is hypervigilant is permanently in a trauma space, constantly listening, looking for and anticipating potential threats.

This develops when a parent is not reliable or predictable - stable even. A child growing up in that environment learns to read their parents non-verbal cues. They must attune to their breathing and movement. They must predict their mood in order to stay safe.

Hypervigilants are highly attuned to the emotions of others, their tone of voice, facial expression, tension in the body, the weight of their footsteps, the pace of their speech, the inflection in their voice. There is nothing the hypervigilant doesn't notice, but they often don't realise they're taking it all in. They just respond to the environment, the signals, whatever is going on around them, without knowing that they are making adaptations to their own behaviour.

Constantly, tense, on guard and exceptionally aware of their surroundings, hypervigilant people automatically tune into surroundings, whether that involves others or not, assessing for danger and potential escape routes, which makes public spaces and large groups particularly exhausting for them. They often experience extreme fatigue after such events without realising why.

The Impact

An adult who has grown up with emotionally abusive parent will typically have anxiety, depression, social anxiety, suicidal ideation, self-abandonment, low self-esteem, a toxic inner-critic, a lack of identity, relationship difficulties. Every single relationship will be impacted by their childhood and they are likely to have unhealthy friendships, as well as romantic and work relationships that look similar to the dynamic they had with their emotionally abusive parent. And yet, they will not understand that they are repeating a relationship pattern, a model of love they learned in childhood that they are now taking with them in adulthood.

The child of a narcissistic parent is taught to put everyone else first and consequently feels chronically guilty and shameful when they try to stand up or advocate for themselves. They lead a life in which they do everything for everyone else and never believe it's enough. They walk through life always thinking they are the problem, never considering the possibility that it could be someone else.

They have a harsh, often toxic, inner critic constantly reminding them they are not enough. Berating them for being defective, less than, broken, fundamentally flawed. They feel tolerated, not loved, and will apologise and compensate for their very existence with everyone they encounter.

When someone grows up in a narcissistic household these behaviours become normalised. The repetition of these patterns means the baton of trauma is passed on from generation to generation until someone decides to change it.

We wrote You're Not The Problem to help clients and therapists recognise emotional abuse and narcissistic traits and behaviours. We show the reader the immediate and long-term impacts of those behaviours and strategies for healing.

Helen Villiers and Katie McKenna are the authors of You're Not the Problem