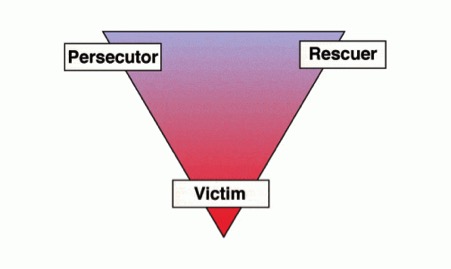

I imagine a lot of families will recognise the patterns I am about to describe. I have seen them played out in my own family and the families of clients I see on a daily basis. Introducing, The Drama Triangle:

Each of these positions in the triangle is a role rather than a person. Indeed the same person can move around the triangle switching roles as they go. The important point to make here is that they don't actually escape the triangle as they do this, they just shift position. They are trapped.

We should start with the central victim role. This is what we call the 'poor me' position and it is where we feel helpless, powerless, at the mercy of events, people, situations, circumstances. We blame others and take no responsibility ourselves for resolving the situation. We can't, because we believe ourselves to be unable to do anything about it. Of course it is possible that we cannot. After all, there are lots of things we can't control but we have the choice as to whether we want to be a victim and be controlled by the person or situation. We can still choose how we respond.

"In the position of victim you become hyper-vigilant, always anticipating the next bout of suffering. All you see in life are problems. And these problems, whether they are people or circumstances, become your Persecutors, the perpetrators of your misery. The victim role isn't maintained in a vacuum. Some person or thing must wear the persecutor label." -The Power of Ted by David Emerald.

Faced with the same situation - divorce, unemployment, illness - people will respond differently. Some will choose to be a victim and be helpless, looking for a rescuer, and others will step away from this victim option and take responsibility for what they can do. So victim isn't defined by the situation but what we choose to make the situation mean for us. This will depend on the beliefs imprinted during your early childhood. Youngest children often feel like the victim in the family with power taken from them by older siblings. Older siblings tend to be the rescuer, sorting out the problems of their younger siblings.

As the victim never takes responsibility, they also never gain the self-esteem that comes with resolving one's own problem.

In fact, the person who does, is the rescuer. That person who sees themselves as the 'fixer' the 'go to' often mum or dad is the one who gets the satisfaction of fixing the problem.

The rescuer intervenes to deliver the victim from the persecutor and in so doing communicates to the victim that they cannot do it alone. They need the rescuer. Just as the persecutor can be a situation or a person, so too can the rescuer. Rescuers can come in the form of alcohol, food, drugs, sex, but as we all know as we drown our sorrows in wine or cake, we then feel remorse and shame about what we've done and return to the 'victim' role.

Rescuers enable victims to stay small and dependent. They fear loss of purpose so they are on the look-out for a victim to rescue because it gives them meaning and a sense of importance, "where would you be without me?" and a sense of feeling good about themselves... until they feel they aren't being appreciated and off they go to victim; "why is it always me who organises the teacher's gift?", "why am I the one left waiting to lock up?" and so on.

I'm sure you can already see how relevant this is for families.

Mum has worked hard all day, she's tired and still has to make a meal for the family and she feels put upon. She feels resentful. Why isn't she supported? Why don't the kids clear up after themselves? She has taken the victim role. The kids come in and leave their shoes scattered all over the room and ask what there is to eat. Maybe they start bickering and shouting. This tips mum over into persecutor because she is mad at them, they don't appreciate all she does. They now become the victim; they don't understand what they've done wrong. They're just being kids. Now mum feels bad, she is back to victim because she still hasn't had her needs met and now she's feeling bad as well.

This situation could have been avoided if she had calmly expressed her needs, "put your shoes away and find yourself a snack while I get on with making dinner" or better still "tidy up your shoes, and I'm going to chill for a while before I make supper."

You don't even need three people to have a Drama Triangle, you can have one all on your own!

I've certainly found myself being victim. "Why am I so overweight?" I wail at myself in the mirror. I blame my work, having sat down at my desk all day. "I don't have time for exercise, I work so hard." Work or my addiction to it is the persecutor. So I then make myself a pizza and have a glass or red and 'rescue' myself. But, then I feel bad - back to victim and blame my lack of willpower this then is the new persecutor ; maybe it's my mum's fault for bringing me up so I felt I had to achieve in order to please her another new persecutor ? Maybe I have a chat with a friend who 'rescues' me by telling me how she admires my work?

In the Drama Triangle no-one is expressing their needs.

So how do we escape?

- Step 1