"Are we going to be head of rugby?" a well-dressed mother self-consciously jokes with another. They stand by their BMWs in the forecourt of a prep school accepting their tiny sons for the first time.

Trunks have been carried in, housemasters have made brisk reassuring comments, and the 'settling in period' has begun. There are no tears. The scene comes from a BBC 40 Minutes documentary, made 20 years ago, called The Making of Them, in which young boarders were discreetly filmed over their first few weeks at prep school. It is available on YouTube, but careful: it will make you weep or angry, or both.

Self-reliance and success are on the curriculum; feelings and empathy are not.

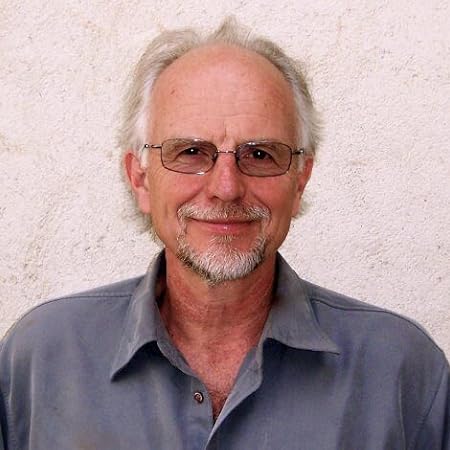

I borrowed its title for my first book, describing psychotherapy with adult ex-boarders, whom I named boarding school survivors. An ex-boarder myself, I have spent 25 years pioneering an understanding of how children adapt to institutionalisation, dissociating from their feelings and developing a pseudo-adult character, the defensively organised Strategic Survival Personality, which severely limits their later lives. To survive without touch, love and care they have to reinvent themselves; as adults they may never regain or learn emotional intelligence, for self-reliance and success are on the curriculum; feelings and empathy are not.

If they ever seek therapy, they make very difficult clients, so I now concentrate on informing other professionals about the syndrome. Forced to become afraid of their own vulnerability, to have contempt for anything soft, ex-boarders are inevitably unskilled at intimacy, relationships and parenting, retaining ambivalent attitudes about home, family, and - especially - women, or femininity, if they are female.

Later in the film, we see Freddy, nine, back at home on his first half-term: "If anybody ever asked me ... 'do you think you should stay with your mummy, or... or ... do you really want a good education?' I wouldn't be able to answer that question ... I wouldn't ... no ... not really."

Nearly two-thirds of the current British cabinet went through public school and Oxbridge before drifting seamlessly into top jobs.

Boarders put on their brave faces and become, as my colleague Joy Schaverien says, "lost for words." A powerful double-bind affects them: if they admit they'd rather not be sent away, they risk upsetting their parents who have forked out huge sums, currently in the region of £30,000 annually, and from whom they have learned what fun it will be and what a privilege it is. And socially, it is a massive privilege. Nearly two thirds of the current British cabinet went through public school and Oxbridge before drifting seamlessly into top jobs. The boarding tradition remains the single most powerful tool for establishing a family on the right side of the tracks in a class system that sets us apart from our European neighbours. This cannot be properly spoken about in Britain, where it is enshrined as an elite tradition that exerts a powerful, but little recognised, life-long effect on those who grow up there.

Bullying is endemic and inevitable in these institutions full of abandoned and frightened kids. Ex-boarders' wives often experience it too, but the British public normalises it. Jeremy Clarkson, 'joking' that he'd "have them [striking public-sector workers] all shot," was even defended by David Cameron. No prizes for guessing where either man learned his style. Bullying is a survival strategy at public school, just like keeping your head down, or becoming a charming Hugh Grant-like bumbler, or keeping an incongruously fixed smile in place, like Health Minister Jeremy Hunt.

Ex-boarders regularly develop a brittle, defensive character while appearing confident.

Psychologically, the privilege of boarding school is double-edged: it creates both shame that prevents sufferers from acknowledging their problems, as well as an unconscious sense of entitlement. This accounts for why ex-boarders regularly develop such a brittle, defensive character while appearing so confident. The cracks show in Cameron, patronisingly insisting that Angela Eagle MP should "Calm down, dear" during PM's Questions - as if she were the one flustered and not he. Psychotherapists will recognise this as dissociation followed by projection.

Boris, however, is so confident he needs neither surname nor adult haircut; he trusts his buffoonery to distract the public from his bullying. Andrew Mitchell's bicycle is a symbol of the deep division in British society that this entitlement creates. This sense of entitlement compensates for all those years without love, touch and family, for the stress within the personality and the lack of emotional, relational and sexual maturation.

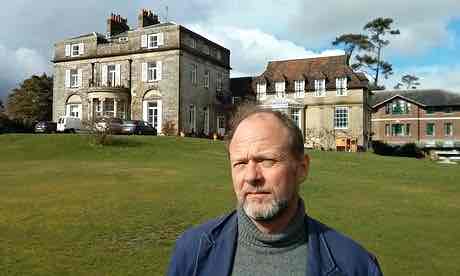

In my latest book, Wounded Leaders, I trace the history of entitlement and the negative attitude to children to colonial times. I point out the fear and grandiosity that characterised what I call the Rational Man Project, with boarding schools as an industrial process to churn out stoic, superior leaders for the Empire. Then I include recent evidence from several neuroscience experts that shows what a poor training this actually is. In short: you cannot make good decisions without emotional information, you cannot grow a flexible brain without good attachments, you cannot read facial signals if your heart is closed down, and you cannot see the big picture if your brain has been fed on a strict diet of rationality.

They cannot conceive of communal solutions because they haven't had enough belonging in a family to understand what that means.

Unreconstructed ex-boarder politicians have had the worst preparation for leadership. They cannot make good political relationships or project global authority like an Obama, because they are run by the fearful, abandoned boys inside of them and need someone to bully. They cannot conceive of communal solutions like an Angela Merkel, because they haven't had enough belonging in a family to understand what that means. Europe is a huge problem, because they cannot conceive of being part of a greater whole as team players, but only as leaders.

From France, where I spend half my time, our class system seems absurd, our boarding schools archaic, and our politics arrogant. Sometimes people ask me: "Why do you think you can lead Europe when you haven't even joined?" At other times: "Why do have children if you then send them away?" Obvious questions really, but their connection is complex. Sometimes I feel a bit like little Freddy and can't answer - well, "not really."