Is Your Brain Male or Female?

BBC Horizon's recent programme, “Is your brain male or female?" made a valiant yet narrow minded attempt at measure and reason.

I offer this blog to anyone who remains as riled as I by Michael Mosley's acceptance of Simon Baron-Cohen's carefully paired claim that, “The male brain is predominantly hard-wired for understanding and building systems," and, “The female brain is predominantly hard-wired for empathy."

The first evidence cluster is derived from animal behaviour. For example, male great apes engage in more play fighting than female great apes, and female great apes show more interest in babies; male rats find their way through mazes more quickly than do female rats - though higher levels of testosterone improve female rats' ability to find their way through a maze. But hormones constitute software not hardware; they are an environmental influence.

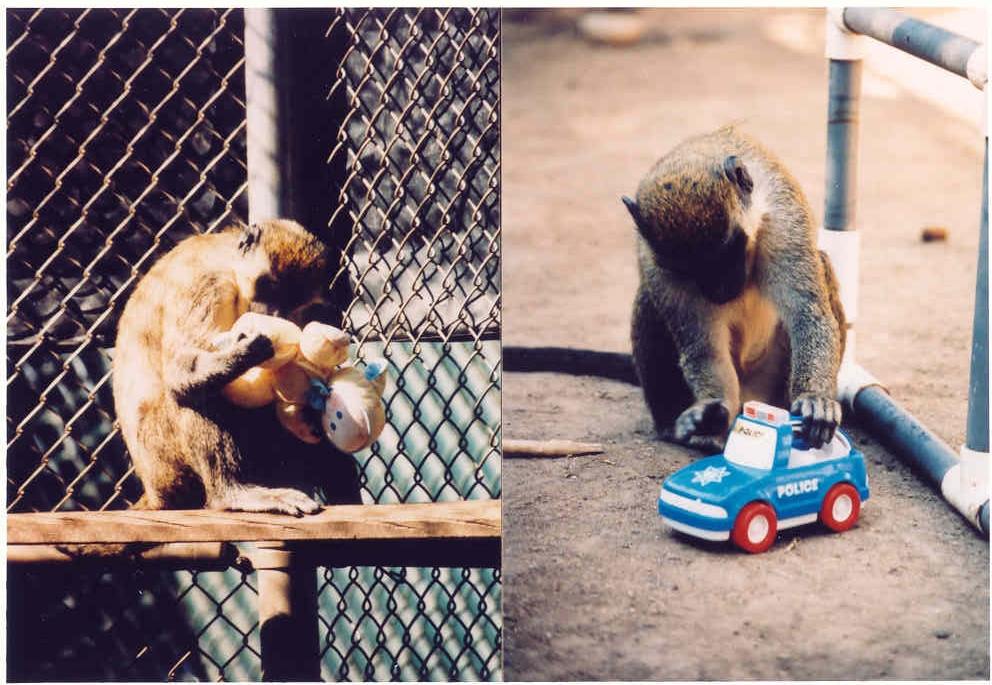

Evidence from animal behaviour is attractive to those claiming “hard wired" differences because animals are outside human culture. But how are they then relevant to human behaviour? Melissa Hines' observations on toy preferences among monkeys are fascinating and delightful, but give us no idea about these preferences mean to the monkey mind. The leap (which Hines herself does not make) to a systematizing/empathizing distinction is again difficult, since animals do not in any obvious way understand or build systems.

Hormones constitute software not hardware; they are an environmental influence.

A key argument rests on a study of one-day-old infants showing that male babies were more likely to focus longer on a mechanical mobile, and female babies were more likely to focus longer on a human face. The persistence with which Baron-Cohen argues that empathy is distinct from systematizing is remarkable, and leads him to strange places, where boys, in visual search tasks administered by psychologists, are better at noticing detail, but where girls, less quick to notice detail and change, are somehow better at reading changes in mood and emotion in faces. But reproducing this study is tricky, partly because it is very difficult to track the very short attention span of a one day old infant.

Evolutionary arguments used to support the propositions that "the female brain is predominantly hard-wired for empathy" and “the male brain is predominantly hard-wired for understanding and building systems," bring us back to the human arena. In hunter-gatherer societies, system focus allowed men to test the effectiveness of arrows, and to understand weather and season systems. Spending long periods of time alone, they could skimp on empathy development. Women, on the other hand, stayed together, made friends, had children, gossiped and were good at reading the feelings of their mates so they could be good partners to their men.

Where is the evidence for female empathy as soft and shapeless feeling?

In women's daily work as gatherers, they used implements for digging, weaving, cooking. Are these lesser tools than those used in the hunt? Weather systems and seasonal systems would be as important for the gatherers as for the hunters; and if women were good at gossiping, then they were good at understanding and tracking social systems. Repeatedly, those who argue brain differences strip away structure from things women do and pack structure into accounts of what men do. However, if the emotionally-challenged Rob in Nick Hornby's High Fidelity exhibits typical male systematising in his classification of musical tapes, then what is the (stereo)typical female Cher doing in the film Clueless when she sets up computerised classifications of her clothes by style, colour and co-ordinates?

And what happens to the cognitive element in empathizing when it is said to be hard-wired in the female brain? Empathizing skills include not only sympathy for others; they also include understanding that gives the power to manipulate and plot. Where is the evidence for female empathy as soft and shapeless feeling? A common argument comes from girls' and boys' play and conversations. It is said that 99% of girls play with dolls at age six, compared with just 17% of boys, and, it is said, doll playing is the opposite of rule-based activity. But close observation of girls' play reveals a deep and subtle rule book, and their gossip weaves and disrupts highly complex social systems.

Empathizing skills include not only sympathy for others; they also include understanding that gives the power to manipulate and plot.

Empathy involves high levels of attention to detail and assimilation of different contexts and systems. Someone skilled in empathy does far more than label a facial movement as a smile or a frown. Analysing a smile as false or genuine, for example, involves the ability to recognise something as a smile, and then to note minute differences in the muscle work on the face. If boys perform better on visual search tasks administered in psychological studies, and girls are quicker to note changes in the human facial map, then the visual search tasks administered in psychological studies should be reassessed.

We can see a more imaginative and coherent model in Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse. Mr Ramsay - socially awkward, emotionally isolated, stuck on facts and linear thinking (he models philosophical thought as an alphabetical progression) – lives in complementary contrast with Mrs Ramsay who "knew [her son's feelings] without having learnt"; but Woolf shows that "knowledge without having learnt" is derived from observation of minute detail and access to multiple contexts. She is the archetypal empathiser because she is adept at understanding complex systems.

For further input into the debate check out TED Blog 'On Nature versus Nature' by Daniel Colón-Ramos here and Psychology Today's Tania Lombrozo's article 'Explaining Gender Differences' here.