How Well Do you Know your Family?

How often do you talk to your relatives? I mean, REALLY talk to them?

I don't mean “have it out” with them, but give each other time to think about things that matter to you both, and really listening to each other? If you're like most people, the answer is probably: not that often.

It's odd, if you think about it, how much energy some people devote to finding dusty facts about long-lost relatives (Richard III being a notable example) while overlooking the treasures available to them from living relatives – whose stories could make our toes curl, tears flow, or heads fall to the floor with laughter.

As a journalist and theatrical improviser, John-Paul learned long ago that absolutely everybody has amazing stories to tell. And Harriet, who edits the Guardian's Family section, feels the same. We've spent years gently teasing stories out of people - but we know that others sometimes find that difficult.

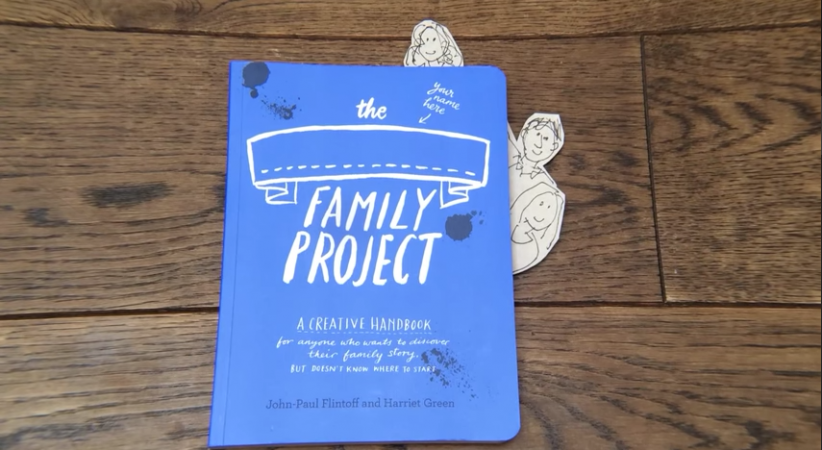

So we wrote a book together, The Family Project, to help other people get conversations started in a playful way.

If your family is coming together for Easter, why not fill the bright spring days with some creative exercises? You can do it sitting around a table with paper and coloured pens, or even while you go for a walk. It's useful to capture what you hear, in writing, drawing or with audio – but not imperative.

Taken as a whole, the exercises give you a framework to break down a person's life experience into manageable chunks – and to focus on things that people are likely to WANT to talk about. Who knows what you might discover?

A great family story includes, among the all the sensational events, insights that give a powerful sense of the everyday fabric of family life.

At the end of this post, we've given a few exercises for you to work with, but before you start – a word of warning. Bare facts aren’t enough. The best family stories are skilfully woven through with what the people involved were feeling and thinking at the time.

And it’s not only the big facts that matter. A great family story includes, among the all the sensational events, insights that give a powerful sense of the everyday fabric of family life – the things that usually slip unrecorded into the past. It’s the contrast between the sensational and the everyday that gives each its power to move.

If you don't have relatives with you at Easter, you can do the exercises by yourself – you may find yourself remembering many lovely things you've not thought of for years. But it's always best to do it with somebody else, in conversation, taking turns to help each other look back.

It’s hard to believe until you try it, but talking to a willing and interested listener can yield much more detail – if you give each other full permission to ask questions (you don’t have to answer them all!) Keep asking each other, “What’s so important about that?”

Very early memories

What were they? What were the smells, sights, sounds?

Food

Who did you eat with (special occasions and every day)? Where did you eat, and when? What kinds of food?

Places

Make a map of journeys you took in childhood. Write a long answer to the question: Where are you from? Draw your childhood bedroom, in fine detail. Make a catalogue of the art that hung on the walls at home.

Things

What precious items were lost, stolen or went missing? What would surprise your ancestors, or your descendants, about how you lived?

Beliefs

Who did you get your religious or political beliefs from? Whose got left behind?

Big moments

What were the big and small dramas? Who was involved? Feel free to include things that don’t seem globally significant but were very important to you at the time.

People

Challenge yourself to write a list of 50 facts of sincerely held beliefs about each individual family member. Big things, small things – stick it all down.

After doing this, you may have a sense of a story. If you wish, weave it together into one narrative. Or just let it stand as it is, as a collection of beautiful, heartfelt fragments.

For more ideas, see:

www.flintoff.org/family-project