How We Can Move On From the Stories We Tell Ourselves

We all have stories within us. Most of us have many stories. Sometimes it’s quite difficult to know what our main story is and yet, somewhere along the line, it’s important to know what stories define us. I only fully realised my life’s tale when I was at my Uncle’s funeral last year. As I sat with my siblings in the pub after the service, I realised that a lot of people were looking at us. There was a general murmur going on. Then one of the men, a very handsome and dapper man in his 80s, came over and said to me ‘are you all Patrick’s children?’

That’s when it hit me. I am nearly 51, over half a century old, yet there I was defined, as the child of my father.

My father was one of those men; quixotic, clever, popular, funny, highly successful, very well-known as a publisher, but also an alcoholic. He died 17 years ago, aged only 61, of alcohol-related illnesses on Armistice Day and I can barely look at the red poppies we all wear without feeling tearful.

Yet there I was all these years later, still being ‘Patrick’s daughter’ and I loved it. It made me feel special and important and it also made me feel young. As soon as the handsome octogenarian asked me the question, the decades were shed. His question gave me a connection to something – my childhood, my pain, my own lost years of my own drinking (but that’s another story). Then it hit me that I have used this story, this ‘I’m-a-child-of-an-alcoholic’ to hide behind nearly all my life. I have excused a lot of my behaviour on this as in “Well, you can’t blame me can you? My dad was an alcoholic.” It has made me believe I am allowed to behave in a quixotic way that has made me feel ‘interesting’.

But there was more behind it. There seemed to be some kind of tragic glamour behind it all – there I was, a poor abandoned child with this glamorous but damaged father, a man whose name meant something to many people and there I was, his daughter. I realised I have become very attached to this story.

But recently I have been thinking about why I need this story and whether it serves me very well.

In some ways, I have used it. I have hidden behind it. This story has, to a certain extent, prevented me from fully growing up and taking responsibility for my actions. I have had to accept the fact that I am not just my father’s daughter. I am me, an adult. It has frightened me at times to have to admit this for, if I am not the abandoned daughter of a charismatic alcoholic who died way before he should have done, if I can no longer hide behind this, then who am I? What do I do with this story?

My realisation was that I needed to really look at what this story was doing for me and how I could accept it and yet put it back in the past where it belonged.

So, we all need stories.

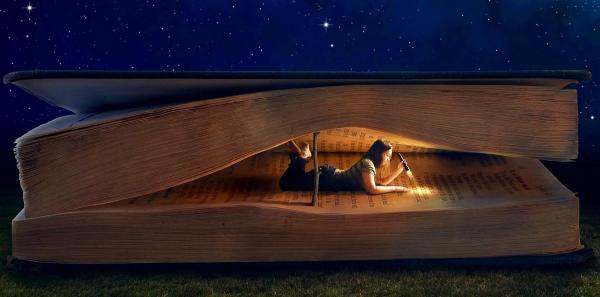

We read them as children. Stories have a purpose. They help us understand things. Children’s fairytales range from the whimsical to the grotesque. My childhood was overtaken by Oscar Wilde’s sad tales of love and loss. My tragic favourite was The Nightingale and the Rose. Scary stories help us overcome and accept our fears. Stories make us safe because, to a certain extent, they inhabit the space between reality and fiction. Children are allowed to feel real fear through reading stories. In the Uses of Enchantment, psychoanalysts Bruno Bettelheim says, “the unrealistic nature of these tales (which narrowminded rationalists object to) is an important device, because it makes obvious that the fairytales’ concern is not useful information about the external world, but the inner process taking place in an individual.”

In this way, I encourage my clients to think about their own stories and whether or not these stories are still working for them. Are they a hang-over from our childhood? There are so many stories that come through the door (which is one of the reasons why I love my job) ranging from the my-mother-never-loved-me through to very painful revelations of domestic abuse and childhoods riven with sadness and a sense of isolation. I hear ‘my sister hated me’ to ‘I was bullied at school.’

All these are valid and there are many times we need stories to make sense of things, just as we did when we were children, however sometimes our stories keep us stuck. For me, I had to look at what my story was doing for me and I worked out that, in many ways, it was reducing me rather than enhancing my life. It’s not that we need to deny our stories. What we believe has happened to us has happened to us, even if other people might see things rather differently. We can only inhabit our own truths. For example, I have three other siblings and their stories around my father might seem very different to mine. So we adapt our stories to help bolster us our psyche. They help us survive.

But there are times when it might work to loosen these stories a bit, to stop the grip of them from defining ourselves for the rest of our lives. The abused girl can overcome that vision of herself as someone who will always be abused. Of course it’s important to work through her past with her and the psychological effects it may well have had on her, but loosening up our stories gives us a sense of hope for the future. I don’t always have to be the daughter of an alcoholic. I might want to be. It has been incredibly difficult and painful to loosen the grip of this definition of myself. It has made me feel safe even though being the child of an alcoholic is a profoundly unsafe place to be. But it has been a place I am used to. To change this story, I have had to face many demons and accept them as part of me.

We grow into ourselves and who we are. All those stories are with us and alongside us but they don’t need to define us. We can hold them close and honour them and thank them for the role they have played in our lives and how they are woven in to the tapestry of our very beings. And then we can move on and find other stories, one that suit us more than those in the past.