How to Meditate: Discovering Headspace

In his book Headspace: 10 Minutes Can Make All The Difference, Andy Puddicombe writes: "This is meditation, but not as you know it. There's no chanting, no sitting cross-legged, no need for any particular beliefs… and definitely no gurus."

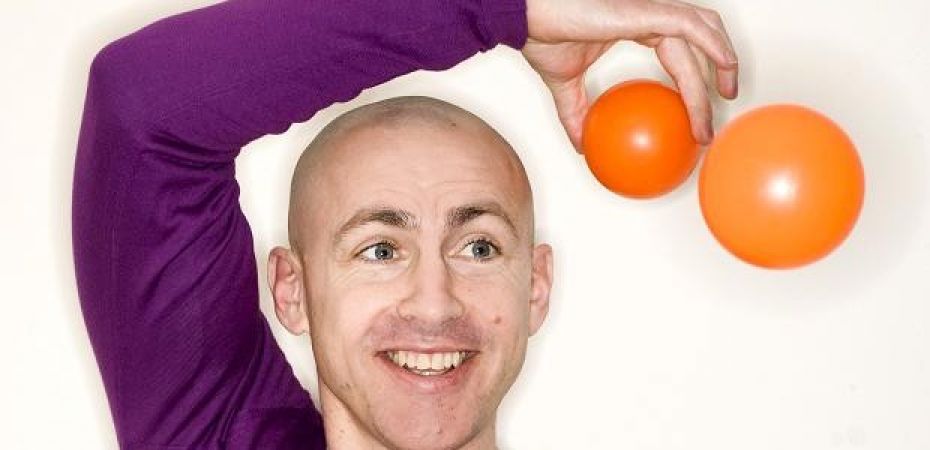

This, then, is Meditation 2.0, aiming to free the practice from its hippy associations . Puddicombe is mindfulness's first poster boy, a former monk and circus trainer, who boasts good bone structure and an Abercrombie & Fitch dress sense. The New York Times has already suggested he is "doing for meditation what Jamie Oliver has done for food", and his Headspace website and app is revitalising a format once viewed as rigid and full of stricture into something so malleable, we'd have to hunt out an excuse not to do it.

As Dr David Cox, Headspace's chief medical officer, later tells me: "The whole point here is to make something - a tool that clearly works - as accessible as possible to as wide an audience as possible."

Headspace launched in 2010. It now boasts over one million subscribers worldwide.

The New York Times has suggested Puddicombe is "doing for meditation what Jamie Oliver has done for food"

I was introduced to Headspace by a friend who had come across it on a Virgin flight (Puddicomb has corporate partnership with the airline). To her amazement, it had almost eradicated her previously considerable fear of flying. The Headspace/Virgin connection makes sense: there is something undeniably Branson-esque about the former's website, which is smart and spiffy, and inclusive enough to make you feel like a member of its club. (While you meditate, for example, a little box onscreen tells you how many other people are also using Headspace alongside you. As I write, at 1.30 on a Wednesday afternoon, 1873 people have also set their sandwiches aside in favour of a little quiet time.)

What it offers is a daily guided meditation you can take at your desk, or on the go through your earbuds. One can subscribe on a monthly basis for a fee, but there is also the introductory Take 10 course, which is free. Puddicomb is the guide, and he sounds pretty much the way he looks: like the kind of bloke who'd know how to erect a garden shed with minimum fuss. His voice does not strive for an over-egged, osmotic calm. Rather, he is down-to-earth and practical. He tells you to close your eyes, to breathe deeply, to count your breaths. At the end of the 10 minutes, he asks, "So, how was it?"

According to Dr Cox, the rise and rise of mindfulness is no mystery. "It is the right antidote at the right time," he says. "Everybody is talking about society being affected by hyper connectedness, 24/7 working patterns, social media, people being addicted to their phones. And the scientific community is beginning to realise that this is having very specific effects on people, particularly in the Western world.

"Evolution is of course a wonderful thing, and we will adapt," says Dr Cox, "but it's a slow process. What has happened in our society recently has happened on a very fast timescale, and so our brains have not yet adapted to cope. And so right now we have an uncomfortable disconnect, and are suffering the stresses as a consequence."

I set my phone to silent, and turn it face down, so that when I do peek - which is pretty much inevitable - I won't be able to see the tell-tale flashing of my BlackBerry's red light, alerting me that a message or, more tantalisingly still, messages, are awaiting.

Take 10 starts with Puddicomb talking us through four separate animations, each designed essentially to illustrate how disturbed our mental states are, and our collective proclivity to see the negative and ignore the positive. Our blue skies are always there, he tells us. Even on overcast days, a blazing blue is waiting just above to reclaim its place. Be patient, he tells us, and wait for the clouds to pass. Because clouds always do.

As he readily confesses in his book, meditation is at first difficult to settle into. The mind isn't used to such stillness, to inactivity. Mine certainly isn't. The moment I instruct it to stop, it deliberately does anything but. It took Puddicomb 10 years of monkhood before he mastered the art, but his conclusion is that we don't all need that amount of quiet in our lives, just more than we currently have.

Meditation is at first difficult to settle into. The mind isn't used to such stillness, to inactivity.

A recent Harvard study revealed that the average adult spends 47 per cent of their waking hours with their attention not on what they are doing. This means that almost half our lives pass us by while we are lost in thought, worrying about the past, fretting over things that haven't happened yet. It is this mind-body imbalance that keeps aggravating our fight or flight response, which keeps the body on high alert, the stress hormones up, the immune system wanting, our health suffering as a result.

And so the point of mindfulness, Dr Cox says, is "to take that little step back and not get quite so emotionally bound up in thought. It's worth the effort."

Over the course of my Take 10, I come to realise that meditation isn't going to come easily to me. I sit and do it every morning, with enthusiasm, but the ripples in my metaphorical pond continue to resonate. I fret about work. I think about what I'm doing next. I pine, ludicrously, for my phone.

Taking that little step back will require work, then. But in Headspace, I might just have found my guide.