The Causes of Addiction: from a Counsellor and Recovering Addict

Most of my clients come to see me because of a crisis in their family or personal relationships. And as such I tend to see many struggling with addiction either themselves or how it affects their significant loved one(s). And whilst it is true that all addicts or alcoholics will have issues with personal relationships, it is not necessarily the case that family or relationship traumas (or any external factors for that matter) are the main cause of their addiction.

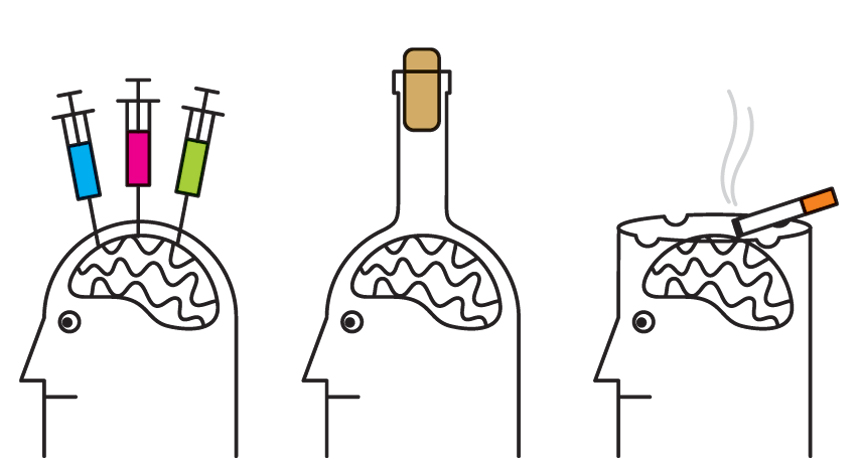

Recent neuroscience research points to addiction as being primarily a genetic condition with addictive potential in place early in life. It is not (as widely believed even in the therapy community) caused by external triggers, traumas or dysfunctional families of origin, though epigenetic studies show that these factors can activate certain gene sequences that trigger addiction (but equally they may not). Genetic factors seem to be strongest down through gender generations (father to son, mother to daughter), but the mechanism is unpredictable. Children of some families escape free from these genes; in others all children – boys and girls are affected. Another equally baffling piece of the puzzle is why we (I speak as an addict many years in recovery) are drawn to a particular drug or behaviour of choice (or combination) rather than another, and why some of us begin early in life and others much later. As any addiction counsellor working in a rehab will testify though, there are almost as many of us who come from healthy functional families (attuned parents, secure attachment, clear boundaries) as those who come from appalling dysfunctional backgrounds.

So what role can counselling or psychotherapy play in recovery from addiction? Firstly, what is recovery? NTA, the National Treatment Agency (part of Gov.uk) believes that addicts completing their planned stay in a rehab have been treated successfully – a view widely derided by those people working at the sharp end of addiction treatment. Many other NGAs and many in the counselling profession define success as abstinence, without any recognition given to the quality of life of the abstinent addict or alcoholic (termed a ‘dry drunk’ in the addiction community).

In common with 12 Step programmes, and charities like Action for Addiction, I would argue that that addiction to drugs is only a symptom of the problem, and abstinence merely the beginning. The real work is on rebuilding all the things on which addiction destroyed - relationships with family, friends and community, nurturing hope, gratitude, spirituality, creativity, a fundamental self-redefinition – in short a truly holistic journey. Jung wrote of the need for a spiritual experience to recovery from alcoholism, long before AA had been started and in a later letter to one of the founders of AA, dated 30 January 1961, wrote that recovery can be achieved "by an act of grace or through a personal and honest contact with friends or through a high education of the mind beyond the confines of mere rationalism."

I see the contribution we can make as therapists in three areas:

- Helping clients come to see the extent of the impact addiction has had on their lives. Denial is generally at an apogee with addicts coming into therapy

- Supporting them through a 12 Step programme particularly in facing the very difficult feelings that arise in Step 4 of that process

- Group therapy utilising peer interaction as well as counsellor interaction

I don’t believe that individual therapy in itself, particularly with a therapist who is not in recovery from addiction themselves, is very effective at providing a client with what is needed to achieve an enduring recovery (as opposed to simply stopping their drug or behaviour of choice through learning coping strategies). Therapy is however an immensely useful adjunct to other more focused well established 12 Step Programme work in Fellowships (it might come as a surprise to many that the Fellowship (AA,NA etc) recovery programmes employ many techniques we would otherwise understand as CBT). Therapy can also address issues that are identified only when a person gets into recovery, that may otherwise destabilise them back into addictive patterns again. Addicts are no different to the rest of the population in this respect – except for one significant issue; that there is also abundant evidence that an addict’s emotional development frequently slows down at the age at which active addiction starts.

I know this is not the view of many therapists working with addiction. But I argue that therapists aren’t comfortable with the notion that for this sort of client, a free fellowship programme provides a better chance of recovery for most than paid for therapy. My reasons are that:

- Active addicts hold a core belief that we are special, that no-one understands us, that if only other people had our lives they too would drink, drug, act out at whatever. We needed to learn that we’re not special at all, apart from having wonky genes, whether epigenetically or through straight forward gene transmission. Even then in the light of what we now know about neuroplasticity, we can create new healthy neural pathways that support a transformed life in recovery. Fellowship groups are great levellers in this respect, whereas one to one therapy (unlike group therapy) tends to unconsciously reinforce the belief of uniqueness, that we are different to other clients.

- Most counsellors set out with objectives to either find the cause of a presenting issue and then resolve it, or work with clients in developing coping strategies and better management techniques to minimise the issue. Identifying the cause is an unsolved puzzle despite the best efforts of years of research funds, and merely offering coping or management strategies often does not remove the obsession to drink, use drugs or act out and leaves an addict in a ‘dry drunk state’.

There are situations and clients in which it can be of immense value – those with dual diagnosis who have a mental health issue as well as addiction. Those clients present a particularly challenging problem.

I should add these days that I am humble enough to acknowledge that I have known some clients who seem to find recovery in the most unlikely places. In the end all I can do in response to addicts seeking help, is to point them to what seems to have worked best for the hundreds of addicts I have worked with in rehabs, but not to claim any kind of exclusive success in therapy.